The basic design for a Dangerous Game Rifle (DGR) was finalized by English gun makers such as Holland and Holland, Rigby, Jeffrey, et al. before the start of WWI. Drawing on the experiences of big game hunters in their African colonies and using the new smokeless propellant, Cordite, these custom gun smiths could now build relatively lightweight rifles that surpassed the stopping power of the earlier 4 to 10-gauge black powder rifles. In the last 100 years, metallurgy, gunpowder, bullet design, and sighting systems have improved exponentially, but in all that time the form of the DGR has changed little.

Many experts feel that there is no need to fix something that “ain’t broke”. I agree that all of the good ideas need to be retained, but I also think that new technologies must be implemented into the basic design to enhance its effectiveness. After all, we don’t drive the same cars or fly the same airplanes that our fathers and grandfathers did. Rifles are no different, and there needs to be some thought put into what changes need to be incorporated to serve the needs of the modern big game hunter.

Here are all the design features I would like to see incorporated into a modern, bolt-action, Dangerous Game Rifle.

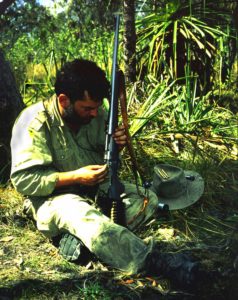

A proper DGR should be designed to operate anywhere on this planet from the Arctic to the tropics, especially for the dangerous game hunter who hunts species ranging from polar bears to elephants.

Furthermore, I prefer my plains game caliber rifles generally be built with these same reliable design features to aid familiarization of function while under stress and to enhance muscle memory.

Many American big game hunters need a rifle that is as rugged and reliable in the Arctic as in the tropics. More American hunters will go to Alaska and Canada than will ever hunt the Dark Continent but they still need a rifle that will work in either environment or terrain. I’m sure that someday we’ll hunt the big game of other oxy-nitrogen atmosphere planets, but today my motto is: EARTH FIRST, we can hunt the other planets later, so let’s think about our needs on our own terra firma.

Military weapon designers understand this need for wide climatic adaptability and it should be in the minds of manufacturers when thinking about building hunting weapons for the US market. Even if a hunter seldom ventures out of his home state, the occasional Rocky Mountain elk hunt can become a life-threatening adventure for the Florida or California hunter not prepared for blizzard conditions and the accompanying bitter sub-zero temperatures.

Perhaps my 21st Century DGR is a quest for the Holy Grail of hunting rifles or I’m tilting at windmills, but I believe that if I could get every one of the following features incorporated into one bolt-action rifle, I would not only have the latest high tech all-around hunting weapon, but, perhaps, the legendary “perfect rifle”.

A hunting weapon consists of three main components: the lock, the stock, and the barrel. While all are crucial to accuracy, as hunters we know if your barrel is flawed, perfection in all else matters naught. With all this in mind, here is my personal wish list of desirable features I want in a 21st-century DGR.

There are many elements to consider in a DGR barrel. These are the ones I consider the most crucial.

The first decision is whether to use a barrel made of stainless or chrome-moly steel. Yes, I know to a traditionalist this is a travesty to even think, much less say …… but in Alaska, despite the best modern lubricants, the weather is renowned for rusting new rifles in a few days because the Pacific Ocean’s salt air exacerbates the oxidation process. The fierce winds blow salt spray miles into the interior and lift it into the atmosphere to be deposited with the rain on the sides of the coastal range. Many hunters buy stainless steel guns to avoid their rifles rusting, however, that could be a serious mistake.

An interesting comment on the Krieger Barrel’s website warns, “It is inadvisable to use stainless steel in very cold temperatures; i.e. below 0 degrees Fahrenheit”. In temperatures below 0 degrees, stainless steel begins to lose its fatigue resistance, increasing the risk of the steel failing from the combination of high-pressure cartridges and minimum contour barrels. Lower cartridge pressure and thicker barrels tend to reduce this problem, but at the end of the day, each hunter must evaluate his cartridge choice, and possible hunting destinations, and make his own decision.

Once you decide which material is best for your particular use, the next decision is whether to go with button, hammer forged, or cut rifling. The German gunsmith Harald Wolf, a veteran safari hunter, and well-known publisher of Hatari Times explained to me why the advantages of cut rifling are worth the extra expense. I always had a hunch that cut rifling was the way to go, but other than my gut feelings, I had no reliable data to back up my position.

As someone who owns Douglas, Hart, and Lilja custom barrels, I have no complaints about their accuracy, but the concept of button or hammer-forged rifling always made me worry about the potential stresses being created in the metal. Button rifling is made by forcing the rifling from the inside out with a button in the shape of the rifling through a bore-sized hole, and the button forms the lands and groves from the inside. Hammer forging is a process where barrels to shaped from the outside using a mandrel that has a reverse image of the rifling formed on its surface.

Like most of these overly technical nit-picking arguments, I just dismissed it as a theoretical issue with no practical negative effects – until I read Harald’s experiences:

“One of my old Ferlach teachers stated that the very best stress-free barrels are cut-rifled. Back then, I did not believe it, as we were all brainwashed by the barrel makers and larger gun factories promoting the superiority of hammer-forged or button-pressed rifling since WW 2. It was nothing but a marketing gig because manufacturing the latter only costs a fraction of labor time-consuming cut-rifling.

Good quality hammer-forged or button-pressed barrels are O.K. if you don’t mount tin-soldered banded swivel and sight ramps to it. As soon as you apply heat (for soldering) the hammer-forged will expand and the button-pressed shrink at this point. The amount would be hardly measurable even by the most sophisticated micing devices, but if you push a soft lead plug down the bore you will notice uneven friction at the points of soldering – and you will never manage to solve the problem by bore polishing.

You can only stress-relieve barrels before soldering barrel bands as the temperature involved is higher than the soldering temperature. Such a barrel might print a superb target with 3 rounds, but if you shoot a 5 to 10-round target you will experience the occasional flyer, up to 4” out of target center. What the gun makers do is simply throw away that spoiled target and shoot another 3 rounds. If the client is shooting and produces a flyer the salesman says “You flinched – take another 3 rounds”! Me and a couple of colleagues re-proved this time and again. The foreman of barrel making at Denel/RSA confirmed the same verbally to me when his boss was not around.”

(MS Outlook, 12/2/2006)”

My original DGR was a .416 Remington KS Custom that was stock from the factory except for the tritium inserts I installed on the sight bases. It had a Kevlar stock, stainless steel receiver, and a stainless steel barrel that featured button rifling.

I have discussed these barrel materials and rifling techniques with other shooters and gunsmiths, and have finally decided to use a chrome-moly Kreiger in .416 Remington in my new DGR project. It is not only cut-rifled but also cryogenically treated. Kreiger takes the raw bar stock down to -3200 Fahrenheit before machining. Cryogenics, as well as moly-coated bullets, have become a major source of argument in recent years among barrel makers, competitive shooters, varmint hunters, and everybody else in the proverbial “Hot Stove League”.

Both sides of the cryo issue have trotted out various expert scientists with exhaustive studies to prove their cases. In the end, they have all agreed to disagree and it has now become a matter of faith. However, one thing is certain about “cryo”– it virtually eliminates stress in metal, thus enabling it to be machined more easily. This saves wear and tear on equipment, makes tool bits last longer between sharpening, and minimizes equipment downtime.

Another thing not many hunters think about is rust-proof bores, although it has been a burning topic in military circles. Many military weapons have chromium-coated bores or Stellite chambers to prevent wear and corrosion from fully automatic fire and inclement weather.

As far as I know, it was the Japanese who pioneered chrome plating their rifle bores to keep them from rusting in the South Pacific. Again, problems with a sea salt atmosphere, but this time combined with the high temperatures and humidity of the rain forest similar to many African hunting destinations.

There have been other bore enhancement technologies over the years, such as Black Star. Most of these were claims of accuracy enhancement with rust prevention as a happy bonus. The pros and cons are still being debated among the brotherhood of bench rest shooters.

A stainless steel barrel in sub-arctic climates provides all the rust prevention any hunter ever needs. But, in extremely cold conditions, there is nothing that has proven better than running an oily patch down the bore of a moly-chrome steel barrel when you return to camp after each day’s hunting then following that with a dry patch swab first thing in the morning.

Hunters seldom see rifles with tritium night sights. Most of the rifles I have seen at the Custom Gun Guild show in Reno, Nevada rarely feature these innovations, although I’ve found only a few with a tritium front sight. This is a serious omission in my experience.

On my first big bore rifle, the first thing I did was to order some night sights that were marketed for Remington combat shotguns. They are imported from Israel and are sold in the States as Meprolight for about $100. These have the usual front sight insert as well as a two-dot insert on the rear sight island. I ordered this setup in the days before everyone had the Internet, and there weren’t any forums and few dedicated safari magazines, so you were pretty much on your own as to what you thought was needed on a DGR.

These Meprolight sights were exactly like the regular iron sights that came standard on the rifle and I installed them in 5 minutes or less. With detachable Warne or Talley rings, I could remove the scope and have an excellent weapon for around the camp at night. When professional hunters either from Australia to Africa would shoot my rifle at night, they would comment about how much they loved those sights and how every rifle should have tritium iron sights installed out of the box. They are so unobtrusive that even the most diehard traditionalists would not object. They are hardly noticeable during the day and are priceless when there are lions and hyenas sulking around outside your tent or you find yourself walking up a wounded leopard. The only drawback is that they burn out after 8 or 10 years and must be replaced.

Other than Meprolight, Trijicon, and Ameriglo, I don’t know of anyone who makes a proper tritium rear sight. The only peep sights with tritium inserts, that I am aware of, are those made for the Ameriglo AR15/M-16 sight. The real innovators here are pistol sight manufacturers who have made them with different colors to differentiate the front from the rear, and with differently shaped inserts to enhance sight picture and alignment. I am sure there is a custom pistol smith in the States who could install tritium inserts into a rifle’s rear sights, but I have not yet located one.

You can get tritium front sights ready to install on a rifle from Paul Jaeger’s old company, New England Custom Guns, which is now run by his nephew Dietrich Apel. Dietrich apprenticed over 50 years ago under his grandfather, Franz Jaeger, in the house and factory where he grew up before he escaped from East Germany. Rumor is that one of their “Universal” series sights has a tritium insert, but there was no mention of it on their website. Perhaps a closer study of Brownell’s catalog will turn up the sight.

Below is a link to Ameriglo tritium sights similar to the ones I have on my .416 Remington KS Safari. The great part about the Remington design is that you can get tritium REAR sights for their island bases. This fact alone was the deal closer for me. It is great to have a tritium front sight, but having tritium rears with it for proper sight alignment has proven itself for me where it counts—in the bush—after dark.

My next mission is to find a pistol smith who will install some tritium inserts into a set of Talley peep sights. If not, then I will have to order Remington rear sight island bases for my rifle, despite the fact that my eyes are getting older with the rest of me and peeps would work better. This is a common problem and something to always consider when recommending sight options.

Krieger Barrels

2024 Mayfield Road

Richfield, WI 53076

(262) 628-8558

Meprolight

58 Hazait Street

P.O. Box 26

Or-Akiva, 30600 Israel

(972) 4 6244111

Ameriglow

5579B Chamblee Dunwoody Road, Suite 214

Atlanta, Georgia 30338

(770)390-0554

Trijicon

49385 Shafer Avenue

P.O. Box 930059

Wixom, MI 48393 USA

1-800-338-0563

(248) 960-7700

Warne

9500 SW Tualatin Road

Tualatin, OR 97062

1-800-683-5590

(503) 657-5590

Robar

21438 North 7th Ave, Suite B

Phoenix, Arizona 85027

(623) 581-2648

Granite Mountain Arms

P.O. Box 72736

Phoenix, AZ 85050

(602) 996-9009

Gottfried Prechtl

Auf der Aue 3

D-69488 Birkenau

Germany

+49 6201 167 88

New England Custom Guns

438 Willow Brook Road

Plainfield, NH 03781

(603) 469-3450

Talley

9183 Old Number Six Hwy.

P.O. Box 369

Santee, SC 29142

(803) 854-5700

Alan Bunn is a hunting publication veteran with a of Bachelor Arts in Journalism from the University of Georgia. He hunts Africa regularly and is an avid hunter with rifle, pistol, shotgun, and bow.