We have the tendency to take things for granted usually for about as long as we have them. It is when we start to lose, or lose completely, what we have that we are brought to the sudden realisation of what we once had which we have no more. Consider hearing as an example. Those of us who love the bush appreciate its unique sounds.

The plaintive cry of jackal ushering in the African night, the haunting call of night jars or the hair standing on end effect brought on by the sound of lions roaring close by, elephants trumpeting, leopards sawing, bees humming, crickets chirping and so we could go on and on.

To lose one’s ability to hear is a tragic loss for one becomes cut off from so much that makes life worthwhile. And what about going blind – how awful that must be. Our ability to see as with hearing is a very, very precious gift the value of which often only becomes apparent when we lose it partially or completely. Those who are deaf say they would gladly give up their sight to hear and those who are blind are often heard to remark that they would be willing to lose their hearing if they could only see again. The fact of the matter is that to lose any or part of one’s sensory abilities is indeed dreadful. Sometimes loss of hearing or sight is progressive. My hearing is not what it used to be. After all my years of shooting (mostly without hearing protection!). I have lost some hearing – especially in my left ear and I struggle to hear high-frequency sounds.

As we get older many of us end up having to acquire spectacles to read or to see at a distance as visual acuity begins to wane due to natural aging processes. Sometimes loss of a sensory faculty can be caused by disease or by inheritance.

I recently came across an interesting case and realised what effect it could have on one’s hunting ability. I had been conducting the tracking module as part of a bow-hunting course when I became aware of the problem. One of the exercises given to students is to follow a prepared blood trail for a distance of about 100m. Exercises begin with an easy-to-follow trail with a lot of bright red blood signs indicating an animal bleeding profusely from an artery and then follow-up exercises become progressively more difficult with infrequent and tiny drops of blood sign. Most students follow the first trail with ease and arrive at the finish point within 5-10 minutes.

On this particular day, I noticed one individual was really struggling. After half an hour he had made no progress at all but was ferreting around aimlessly and not making any headway. I joined him and asked if I could help. He replied in the affirmative. I took him over to where the first splash of blood was that was easily visible pointed it out to him and told him to carry on. A few minutes later he had made little if any progress. Either the individual had no ability to track whatsoever or else there was a problem. I took him to the next blood sign on the trail – once again easily visible – and asked him to point it out to me.

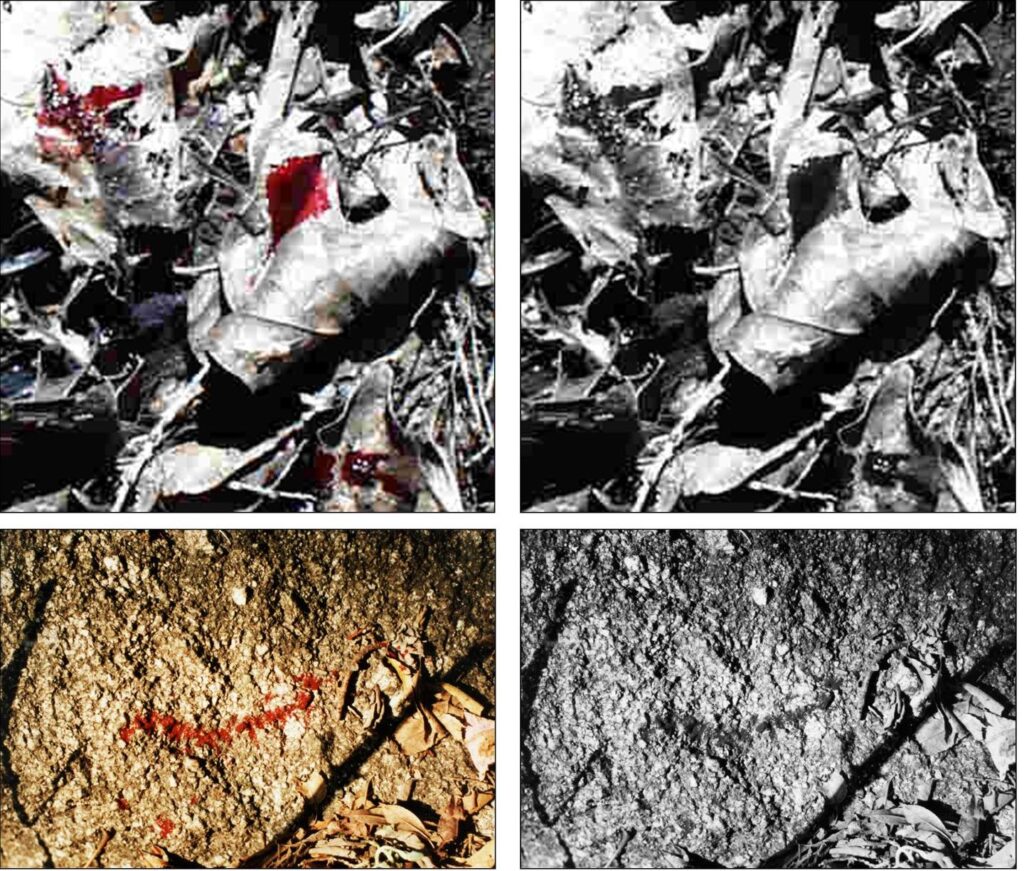

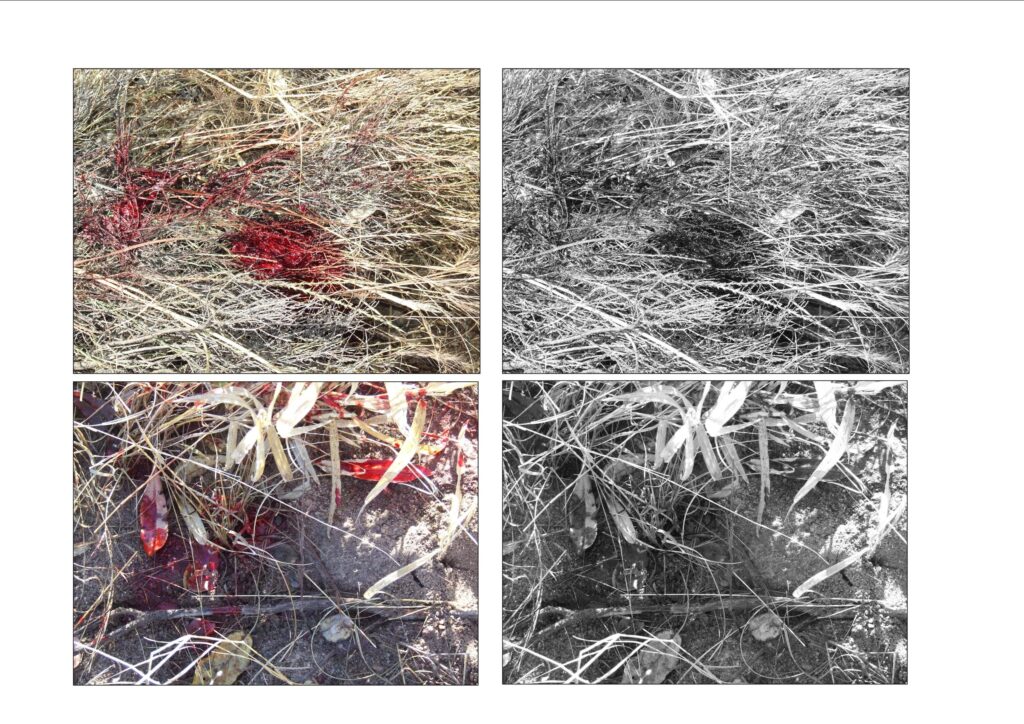

He could not – and then the penny dropped – he was colour blind! This is a genetic visual defect that can manifest itself in the person not being able to see certain colours in the visible light spectrum. The student was red/green colour blind. What we could see as a bright red colour against the background of green grass he perceived as grey on grey and it was invisible to him and hence his inability to be able to follow the trail.

The images above illustrate some examples of what blood signs would look like to a red/green colour blind person. Now the implications of this to the hunter are obvious. He will not be able to follow the blood trail of a wounded animal and will have to rely on a second person, guide, or tracker to assist him.

Being red/green colour blind will also make it difficult to spot wild animals that have a rufous (reddish) colouration. An impala will stand out starkly against a summer green or winter straw-coloured background to someone with normal vision but will be more difficult to spot in a person who has a red/green colour blindness defect.

Most herbivores are also red/green colour blind.

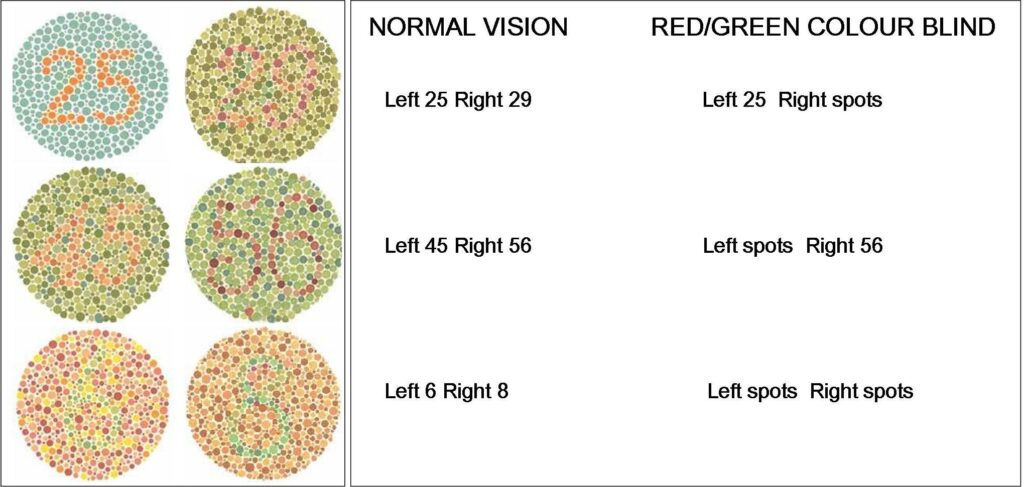

Hunters know how important it is to be able to track a wounded animal from blood sign. We try our best not to wound animals but being fallible human beings we do occasionally “botch a shot” and end up having to try and locate a wounded animal. When an animal runs off after having been shot the hunter will always scout around the spot where the animal was last seen to search for some sign of blood which will confirm that the animal was indeed hit and will then look for the trail of blood sign which in some instances might be quite profuse and in other cases very scant, small and far apart, which will lead him either to within sight of the quarry to allow for a follow-up shot or to the downed animal. We should also be able to follow up on wounded animals by observing other signs such as tracks, broken vegetation, etc. But the substrate does not always lend itself to this type of tracking and this is where the contrasting colour of red blood against a background makes things a little easier – for those that can see the colour red that is. If you are “blind” to the colour red, tracking blood signs becomes a virtual impossibility. How do you know if you are red/green colour blind? A Japanese researcher developed what are known as Ishihara charts which help diagnose the defect. The charts to diagnose red/green colour blindness are shown in the image below.

If you are unfortunate enough to be colour blind to certain wavelengths of the visible light spectrum you will have to rely on someone to assist you when tracking blood signs.

The lesson to be learned from this article? Give thanks – every day – for the faculties that you do have.