When the Excrement Hits the Oscillation.

This is an expression that implies a crisis situation – a worst-case scenario. Professionals are trained to handle “what if ” situations.

- What if the patient’s heart stops beating?

- What happens if one of the aircraft’s engines fails?

- What happens if the boat capsizes?

Training for a crisis prepares the individual to handle the situation when it occurs in real life.

Repetitive practice eventually instills an instinctive reaction to a sequence of recognized events and it is this instinctive reaction that can mean the difference between life and death in many instances.

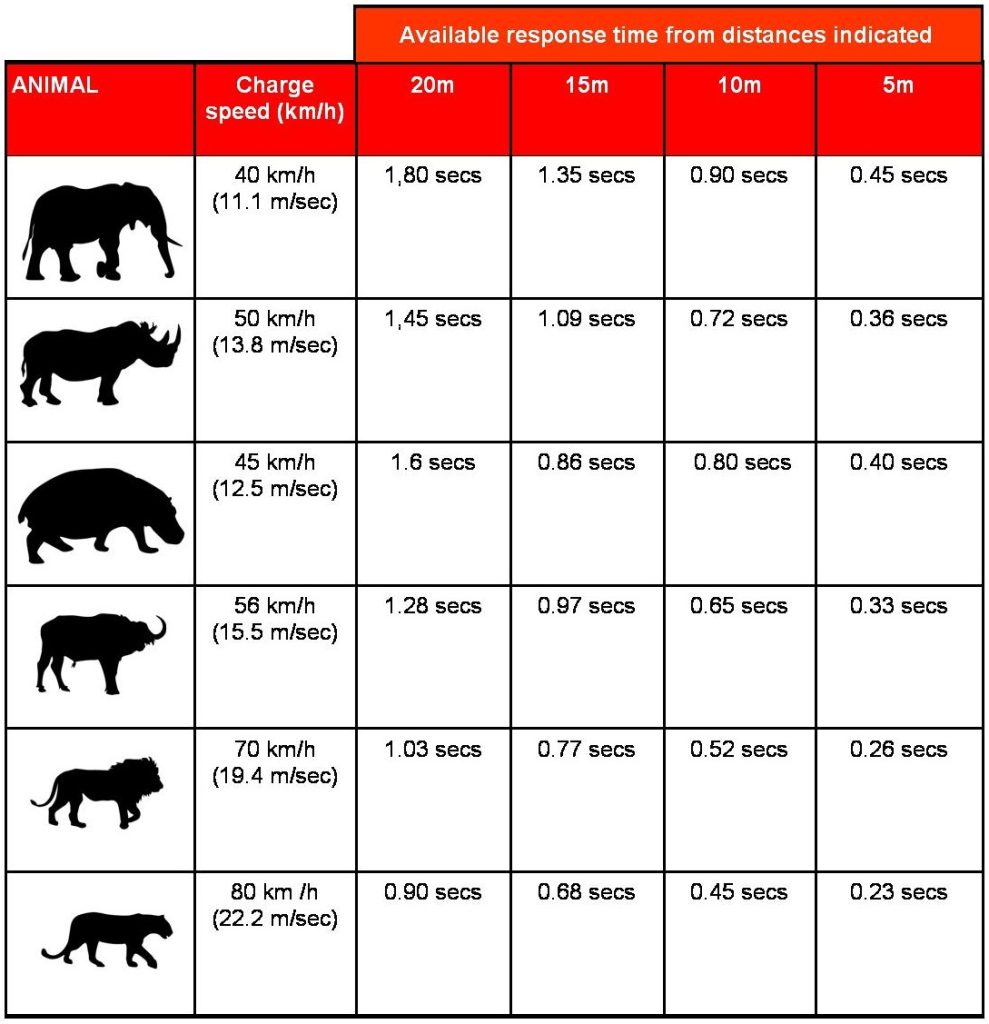

For field rangers, professional guides who operate on foot, and hunters, one of the “paw paw hits the fan” scenarios is being charged by dangerous big game – implying elephant, buffalo, hippo, rhino lion, or leopard. Most charges by one of these animals occur over a short distance giving little time to respond.

There may be a lot of folks out there who say this article does not apply to them because they never intend hunting or cannot afford to hunt dangerous big game. However, you may not actually be hunting one of these animals but may be operating in an area where they occur and find yourself in the unintended situation of having to deal with a serious charge.

Then again, you might be hunting one of these animals and could also be following up on one that has been wounded when you are faced with a life-threatening confrontation. How does one go about preparing for such an eventuality?

Training yourself to handle this type of situation is critically important. If you don’t and the proverbial paw paw does hit the proverbial fan you are likely to panic and that could be the very worst thing you could do.

Be aware

There will be very little time to respond to a charge and you must use a brain shot to drop the animal in its tracks.

If you are participating in any outdoor activity (recreational hiker, leading wilderness trails, on ranger patrol, hunting) in an area where dangerous game is to be found be aware! This is even more important when you are not equipped with the right calibre of rifle to stop a serious charge. Then you must make every effort to avoid confrontation.

This means keeping a very sharp lookout for dangerous game sign and steering clear of dangerous animals. If dangerous animals are spotted, smelled, or heard and you do not have the firepower to stop a charge, keep a safe distance between yourself and potential trouble. Close proximity to dangerous animals is the main cause of serious confrontations.

Don’t let curiosity get the better of you – rather stay away and avoid getting close. This would apply in general to bowhunters (even a 100-pound bow will not stop a frontal charge), unarmed individuals, individuals armed with calibers too small to stop a charge, and those armed with the right calibers but with the wrong type of ammunition.

Even if you are adequately armed, be aware. Know how to identify the tracks, scat, smell, sound, and other signs of dangerous game and how to estimate the age of the sign. At least then when fresh sign is found you will be forewarned of the imminent presence of animals that are potentially hazardous to your longevity and will be keeping a sharp lookout for them.

Walking quietly with the breeze in your face, stopping frequently to listen and smell, and moving slowly will all assist in you spotting a dangerous animal before it spots or becomes aware of you. This is what you want because then if you are not hunting the animal it will give you enough time to take avoiding action and get space between you and the animal. If you are hunting you have a big advantage if you see the animal first as you can then carefully plan your final stalk. What we don’t want is to stumble unexpectedly on a dangerous animal – especially at close range – that is when copious amounts of paw paw start flying all over the place!

Learn about animal behaviour and how to interpret it

Learning about the habits and behaviour of dangerous game is imperative if you are going to be walking in big game territory. Know what their preferred habitats are, if and when they frequent waterholes, times of peak activity, what they eat, territorial behaviour, the protection level of young, predator avoidance strategies in the case of herbivores, hunting strategies of predators, reproductive behaviour, whether they walk singly alone or in pairs and how to identify signs of aggression.

Avoid precipitating situations

If you are not hunting dangerous game or don’t have the firepower to stop a charge – keep your distance. If you purposely put yourself into a situation that makes an animal feel threatened, get too close to animals with young, or make an animal feel trapped by closing off its escape routes you will have to accept the consequences of which serious injury or death are likely probabilities. Don’t go looking for trouble if you don’t have the wherewithal to deal with it.

Practice for the worst case scenario

Assuming that you have the appropriate firearm and correct ammunition to potentially stop a charge by even the biggest animal (i.e. elephant) you must then practise using it.

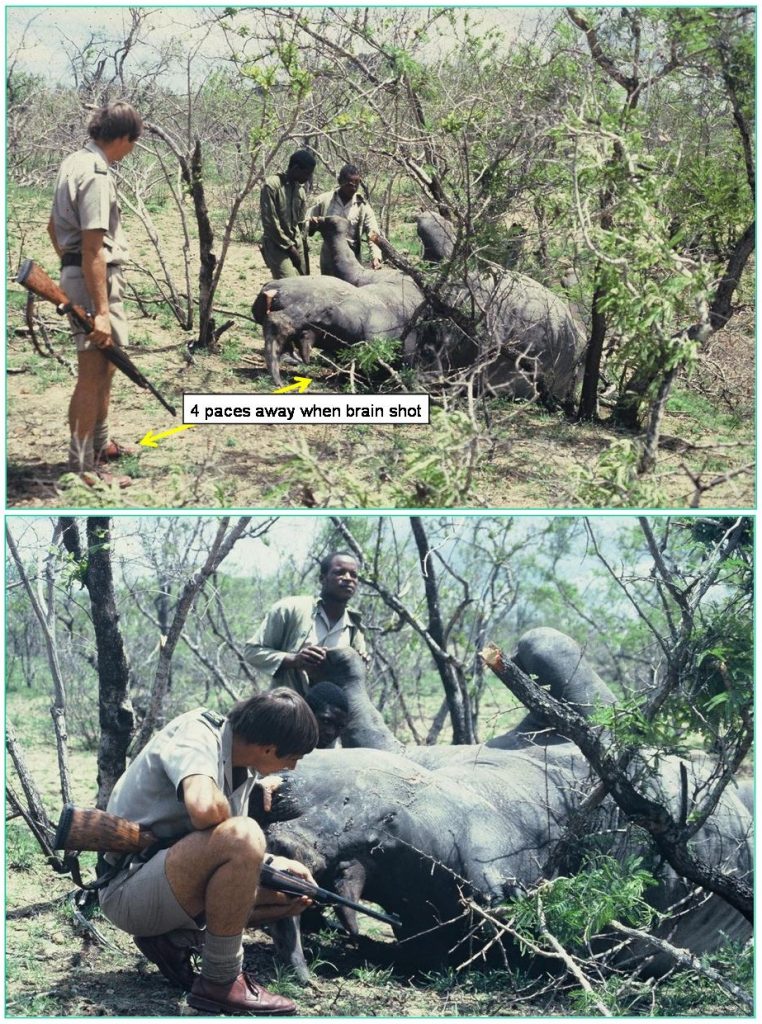

Charges usually occur at ranges of 30m or less so you will be practicing at ranges closer than this because you might not be hunting the animal that charges and wish to give it the opportunity to stop or veer off. You may for example have a license to shoot a lion and are charged by a white rhino. You don’t want to shoot the rhino because it will cost you a heap of money you possibly don’t have and secondly you might find yourself in big trouble with the law.

You would have a hard time justifying having shot a white rhino at a distance of 20 – 30m but would have a far stronger case of self-preservation if you dropped the animal at 5m or less. In this regard, many white rhinos veer off from a charge at a distance of 10 -15m.

Although it is unwise to generalize, dangerous animals have certain behavioral traits when it comes to charges that are peculiar to the species. Some having initiated a charge will follow through with it, others may stop or break away, some give indications of an imminent charge, others charge without pre-warning, and so on.

For the purposes of training and at the ranges you will be shooting at the assumption is that the charge is serious and close enough to believe it will be carried through.

Use the same firearm you will be carrying in the field

Firearms have individual characteristics – they carry, point, and shoot differently. This is true even in exactly the same models firing the same caliber.

One thing that must be understood is that in a charge, split seconds count and you should therefore be thoroughly acquainted with how the weapon you are carrying handles. This is no time to discover the quirks of an unfamiliar weapon.

Practice using live ammunition

Practice using live ammunition of the same type you will be using in the field. You must get used to and comfortable with the recoil of a high-powered rifle and must also be aware of the time taken to re-align a weapon for a second shot after a substantial muzzle climb.

This can be an expensive undertaking given the cost of big calibre ammunition but can be offset by reloading your own ammo. The question also begs the asking: “How much is your life worth?”

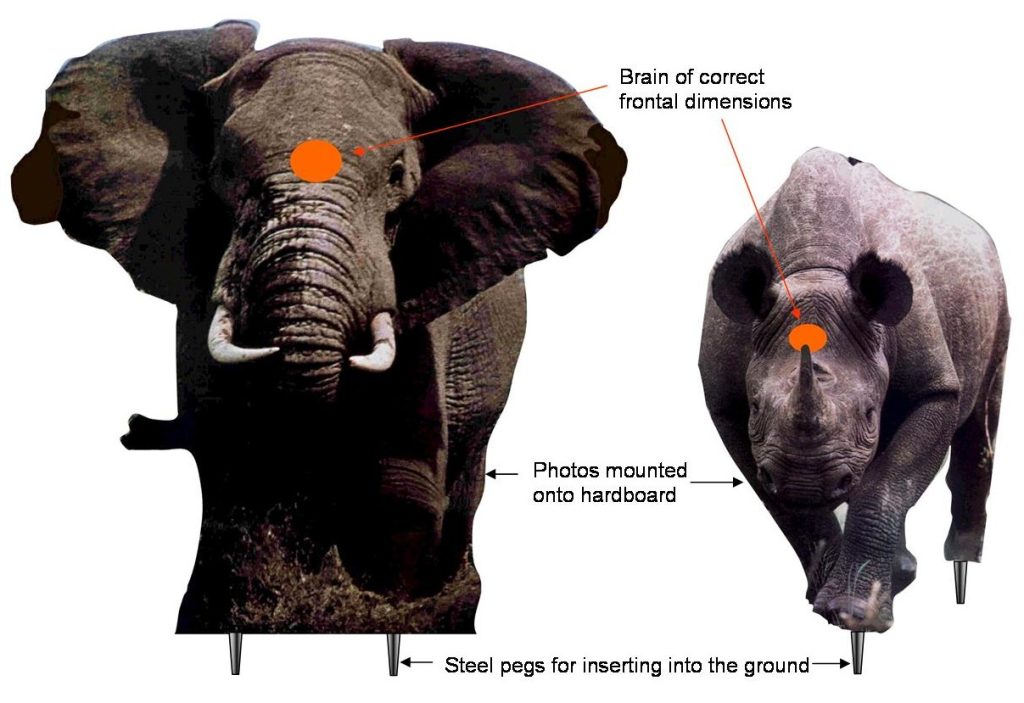

Practice on realistic targets

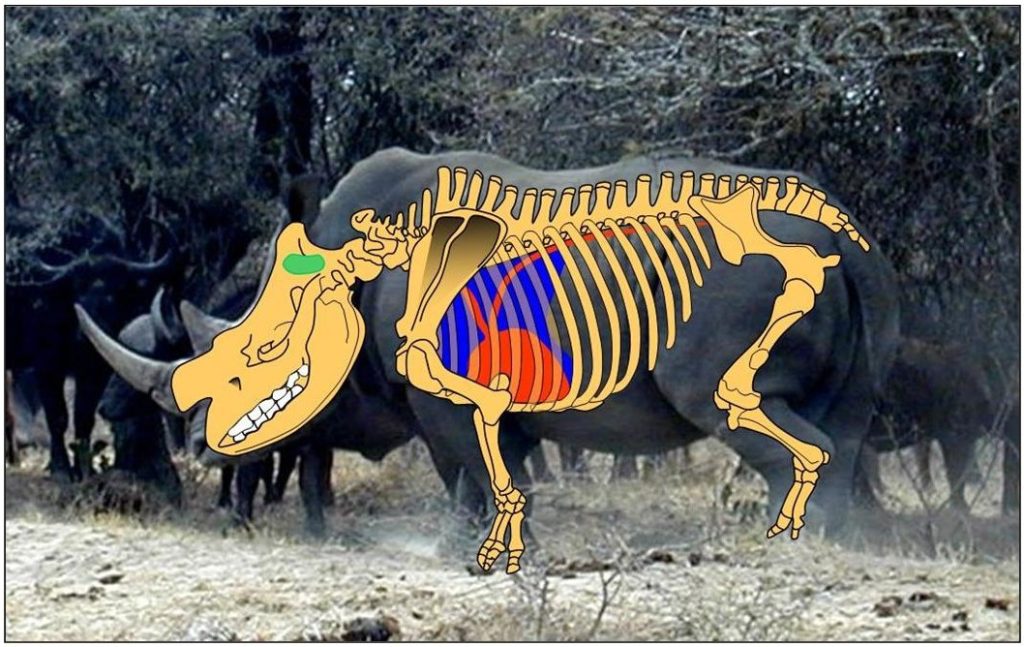

Practice shooting at realistic targets, which should be as close to life-size as possible. This is reasonable with animals of the size of buffalo, hippo, rhino, leopard, and lion. In the case of elephants, this is not practical and the target will be less than life-size. What is important however is that the frontal brain sizes of all animals must be life-size.

Brains should be drawn in initially so that the marksman learns to know its position. Later on, the brain can be lightly pencilled in once the marksman has learned to place shots consistently in this area. Targets should also all be facing on and in “charge mode” as this will be the view from the position of the person being charged.

Photos can be used and pasted onto hardboard to which steel pegs can be inserted into the ground. An alternative is to knock droppers into the ground and tie the targets to these with wire or cable ties. If photos are not available animals can be painted or sketched onto hardboard.

|

ANIMAL |

Frontal cross sectional area of brain |

|

Elephant |

22cm |

|

Buffalo |

11cm |

|

Rhino (black and white) |

11cm |

|

Lion |

5cm |

|

Leopard |

5cm |

|

Hippo |

11cm |

Practice in a natural setting

It is important that you practice in a variety of natural settings so that you can get used to shooting from different positions, angles and elevations. Targets should be placed at a range of not more than 10 -12m from the marksman as this is the sort of range at which a charging animal will be shot.

Also shoot at different times of the day with the sun in different positions (from behind you, shining into your eyes, from the side, and so on) as you can never predict the exact circumstances under which you will have to deal with a charge.

Always keep safety in mind when shooting – know where your bullets will land after having gone through the target. Practicing in a dry riverbed with steep banks is a good option or having a mountain as a backstop.

Understand the importance of shot placement

When a dangerous animal charges you there will be very little time available to drop it and shot placement is critical. Shots to the heart lung area will not drop an animal in its tracks and it will seriously injure or kill you before it dies from loss of blood.

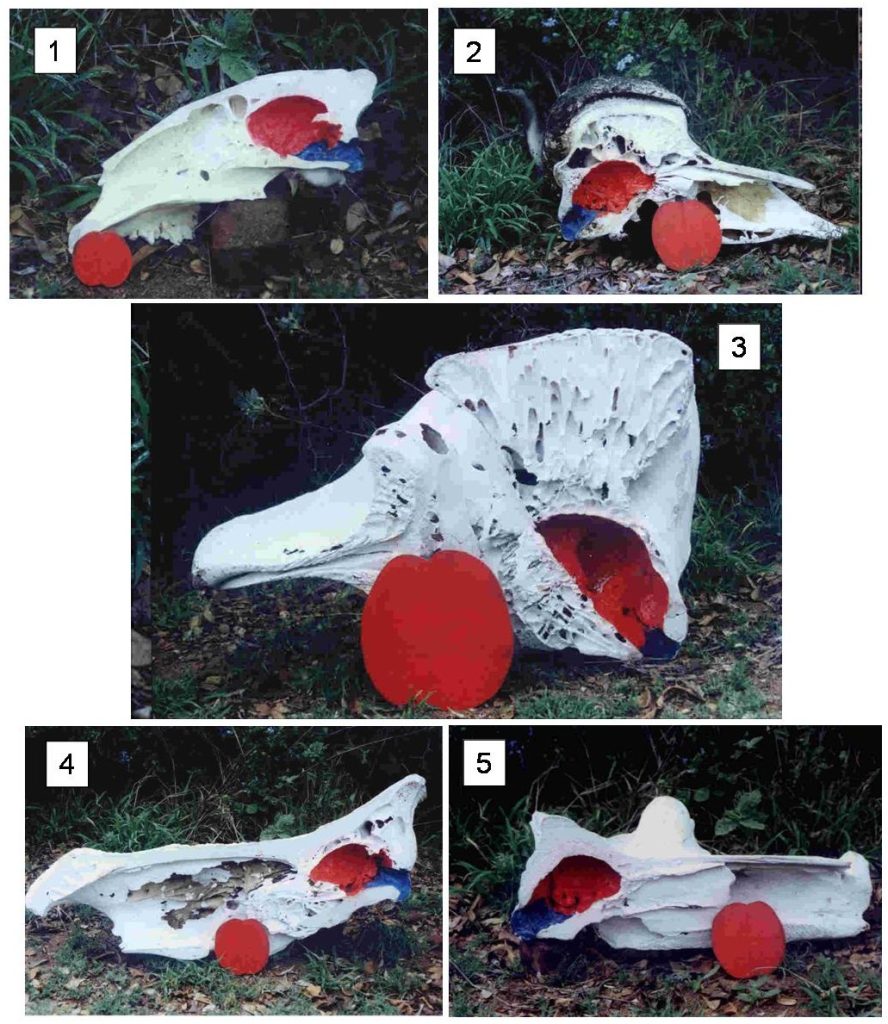

You should carefully study the anatomy of dangerous animals

and know where to place a brain shot from various angles.

The only target you should therefore aim for is the brain.

You have to be thoroughly familiar with the anatomy of dangerous game and know where to place a brain shot from various angles.