The .303 British is one of the most well-known cartridges of the 20th century. It served as the official British military cartridge for more than 60 years and although not popular in America, this rimmed cartridge was very popular for hunting in all the former British colonies. It is still going strong in South Africa, Canada and Australia.

Designed for the Lee-Metford Mk I rifles in 1887, the .303 cartridge was adopted by the British army in 1888. Its 215g bullet was driven by 70gr of black powder to a velocity of 1850fps. When smokeless cordite replaced black powder, the velocity was increased to 1970fps.

Unfortunately the hot-burning cordite powder eroded the shallow Metford-type rifling very quickly and in 1895 the deeper Enfield-type rifling was adopted and from then on the rifles were known as Lee-Enfields.

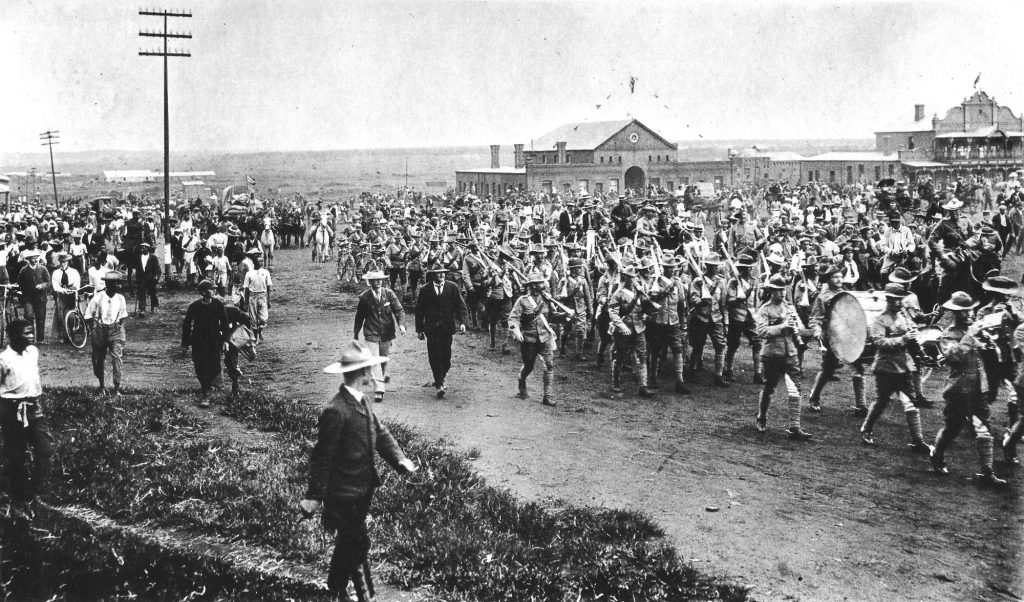

The British used this rifle against the Boers during the Anglo-Boer War of 1899 – 1902. Early in the 1900s when the big military powers of the day (Germany and America) switched to lighter bullets for their service rifles Britain did the same and shortly before World War I the 215gr bullet was replaced by a 174gr spitzer leaving the muzzle at approximately 2440fps.

As all British colonies were issued with .303s, thousands came into South Africa after the Anglo-Boer War and again before and after World War I. Many of these rifles fell into the hands of local farmers and hunters who found the Lee-Enfield reliable and accurate enough for general purpose hunting. Inevitably it was used with military FMJ ammunition which was cheap and readily available in large quantities.

Although deadly on humans, the .303 soon became a controversial hunting cartridge because the military ammunition produced mixed results. The FMJ bullets had aluminium tips which shifted their centre of gravity back. When the Geneva Convention decided that expanding bullets were inhumane for military use, Britain sidestepped this restriction by designing a FMJ with an aluminium tip.

Within the first 100m or so these bullets with their lightened tips were still yawing in flight and when striking a target its “back-heaviness” caused the bullet to cartwheel or tumble through the target, causing horrific damage. On small animals the tumbling bullet often killed like lightning, but if the shoulder bone of a large antelope was struck or a raking shot was taken, the tumbling inhibited penetration and the bullet often failed to reach the vitals.

At longer ranges the bullet stabilized, but then punched a tiny, clean hole through the animal, doing very little peripheral damage and often causing very slow internal bleeding. Many animals thus escaped wounded or ran far before they went down and were subsequently not recovered.

Such conflicting results had as many hunters swearing at the .303 as swearing by it. Overall it developed a reputation as a wounder which was not the fault of the cartridge, but the bullet.

Used with appropriate expanding bullets the .303 is adequate for all non-dangerous game at short and medium ranges.

Under bushveld conditions (out to 150m) a 174gr softnose at 2400fps is good medicine for anything up to and including blue wildebeest and kudu while a 215 grainer at 2150fps will down all game from duiker to eland with ease. Although the .303 is not a long range cartridge for smaller plains game species, 150gr bullets loaded to 2500 – 2600fps will perform admirably on springbuck and blesbuck out to 220m. If you own a rangefinder and are familiar with your bullet/load’s trajectory, taking on small game out to 300m should not be a problem at all.

No manufacturers chamber rifles in .303 anymore, but surplus military rifles can be bought at comparatively low prices and turned into useful sporters. A number of manufacturers still produce ammunition while reloading components are readily available from several companies. Some, like Rhino and Claw, both South African manufacturers, produce premium-grade hunting bullets for this old warhorse.

Although the .303 is quite accurate in properly tuned rifles, especially in ones built on the strong P14 action (a K98 Mauser-type made in America), this rifle/cartridge combination is not meant for long range varmint shooting. Its flexible action and often oversized chamber count against it, but for general purpose hunting any of the old military rifles with good bores will do a stellar job.

Due to the flexible action and oversized chambers full length resizing of cases is not recommended as head separation becomes a common problem. Partial or neck-sizing will make cases last longer and it is good policy to avoid maximum loads. In rifles built on P14 actions handloaders can push the .303 easily into the .308 Win class.

The .303 I own, was inherited from my late father who bought the rifle second-hand in 1952 in the old South West Africa, now Namibia. This old Lee-Enfield MkI of 1902 vintage came with 200 rounds of military FMJ ammunition. I still have in my possession the original licence that was issued to my dad, signed by a Mr Genis. The date 1902 is stamped on the stock and action but whether it ever saw action during the last months of the Anglo-Boer War we will never know.

When I got the rifle the barrel was in bad shape so I shopped around until I found an original BSA barrel in good nick with the same profile as the old one. As I wanted a handy carbine for short-range bush work, I asked the gunsmith to shorten the barrel to 21-inches. In addition to a standard front bead and a wide V rear sight, I had a custom peep-sight made which mounts on the cocking piece. It has a so-called ghost ring aperture, measuring 5mm in diameter. With this sight the rifle will produce 1.5″, three-shot groups at 50m all day long.

My oldest son, Dandrej, gradually developed a love for the old Lee-Enfield and in 2005, at age 15, announced that he wanted to hunt with it. When he handles this rifle, I can often see he is dreaming of an era when it was natural for a young man to roam the bush with a rifle in his hands.

Although American and Norma ammunition are available in South Africa, we prefer to use the local PMP products (factory ammunition and components), which are good enough and much more affordable. When reloading, we use a 174gr PMP softnose in front of 38gr S335 (a local extruded powder, very similar in burning rate to the American IMR 3031). Muzzle velocity out of the 21″ barrel is just over 2300fps – ideal for short-range bushveld applications.

Many modern-day hunters regard the .303 cartridge as inferior because of its old-fashioned, rimmed design and its mild ballistics. They also criticise the two-piece stock and the fact that the Enfield-action is not as strong as most Mauser-types. The slow lock time and the Enfield’s relatively heavy trigger pull are two more drawbacks which count against this 120-year-old veteran. Yet, despite all its “warts” the .303 will still bring home the bacon if the hunter does his bit.

Using an open-sighted rifle with all the drawbacks I’ve mentioned, force the hunter to get close to his quarry, to take extra care and ultimately it puts the hunting back into the hunt. On his first hunt with the Lee-Enfield Dandrej learned just that. We travelled to the Northern Cape to hunt on Wintershoek, a property about 50 miles south of Kimberly. The acacia-studded plains and the broken veld (rocky hills) are very similar to the vegetation and the topography of the area where I grew up in South West Africa and is therefore this part of South Africa is one of my favourite hunting venues.

After working hard for two days, Dandrej managed to shoot a warthog and then decided to go after springbuck. As you probably know, these animals prefer open plains and getting close enough for a shot proved extremely difficult.

I carried a scoped .308 as backup and offered it several times during the hunt to the young Nimrod, but he refused to use it. Finally he told me that he has made a commitment to hunt with the Enfield and by breaking it, he would cheat on himself. Can a father ask for more?

Forced to work even harder than for his warthog, Dandrej learned a lot more about hunting than he would, had he been carrying a scoped rifle. And then our luck changed. On the last day of our hunt we managed to sneak up to a small herd of springbuck, but they stayed so bunched up that Dandrej could not shoot and eventually the group sensed our presence and drifted off.

We followed patiently and eventually caught up with four rams on the far side of a small blackthorn thicket. After some careful stalking we managed to sneak into range and get Dandrej into a shooting position. The springbuck knew we were there, but had not identified us positively, which gave me a chance to set up the shooting sticks for Dandrej. The animals were facing us at a slight angle and when the old Lee-Enfield barked, I heard the 174gr bullet strike with a loud, “dup”. Then I saw how the ram on the extreme right dropped in his tracks.

Dandrej, who shot from a sitting position, jumped to his feet and reloaded quickly, but it was not necessary, the ram was down for good. An autopsy back at camp revealed that the bullet had broken the near shoulder, passed over the heart, destroyed all the “plumbing” above it and then ploughed through the rumen before exiting in front of the far back leg.

This old Lee-Enfield was the only centre-fire hunting rifle my father ever owned and he used it expertly until his ageing eyes made it difficult to use the open sights. I am in my 50th year and shooting with open sights is now becoming a bit of a challenge for me too. However, it is good to know there is a young man who loves to hunt with this old rifle.

I wish them both many happy hunting hours.