Vultures, by any stretch of the imagination, cannot be regarded as good-looking creatures – but they do play a vital role in the greater scheme of things by removing carcasses from the veld.

They can be helpful to hunters, trackers, rangers, guides, and other field staff by indicating the presence of dead animals. But vultures have much more to offer if we know something about them.

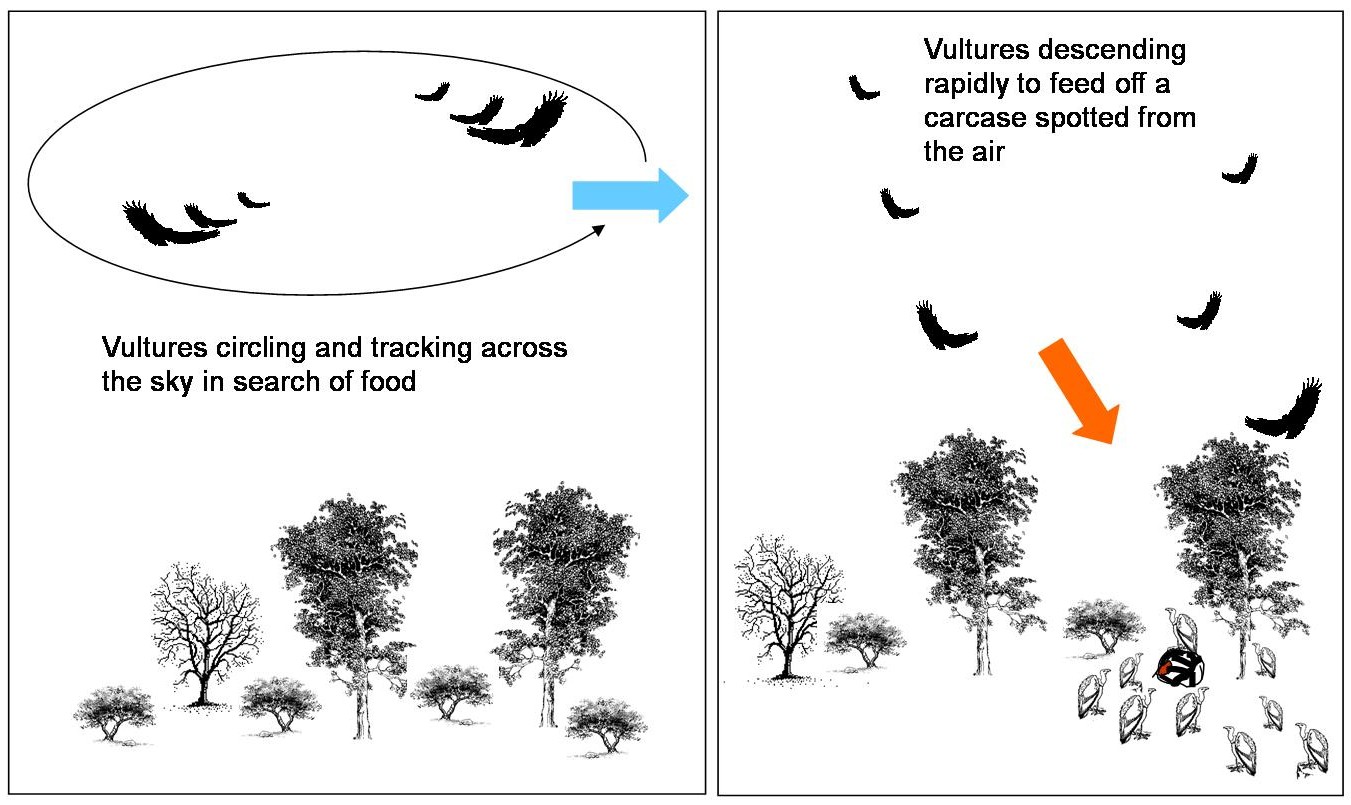

Many people who have not been afforded enough practical exposure to the bush but have watched movies and the square box believe that seeing vultures circling in the sky is a sure indication that something is dead or dying. This is not always the case. We can glean a lot of information from vultures but to do so we must learn something about these huge birds and their behaviour.

Vultures are scavengers that feed on carrion. They eat dead people and dead animals. Because they are large heavy birds they fly best when there are warm thermals to carry them aloft. Once at cruising altitude they can hang suspended on warm air currents with a minimum of effort and cover vast distances in a day in search of food.

Because air is cool or even cold in the early morning or on overcast days vultures will be grounded or “treed” to use a better term and can be found in the uppermost dry branches of large trees patiently waiting for the sun to warm the air which will carry them aloft later on in the day. They can fly if they have to but they are reluctant to do so because of the effort required. Later in the day when thermals start rising, they take effortlessly to the sky with a handful of powerful wing beats.

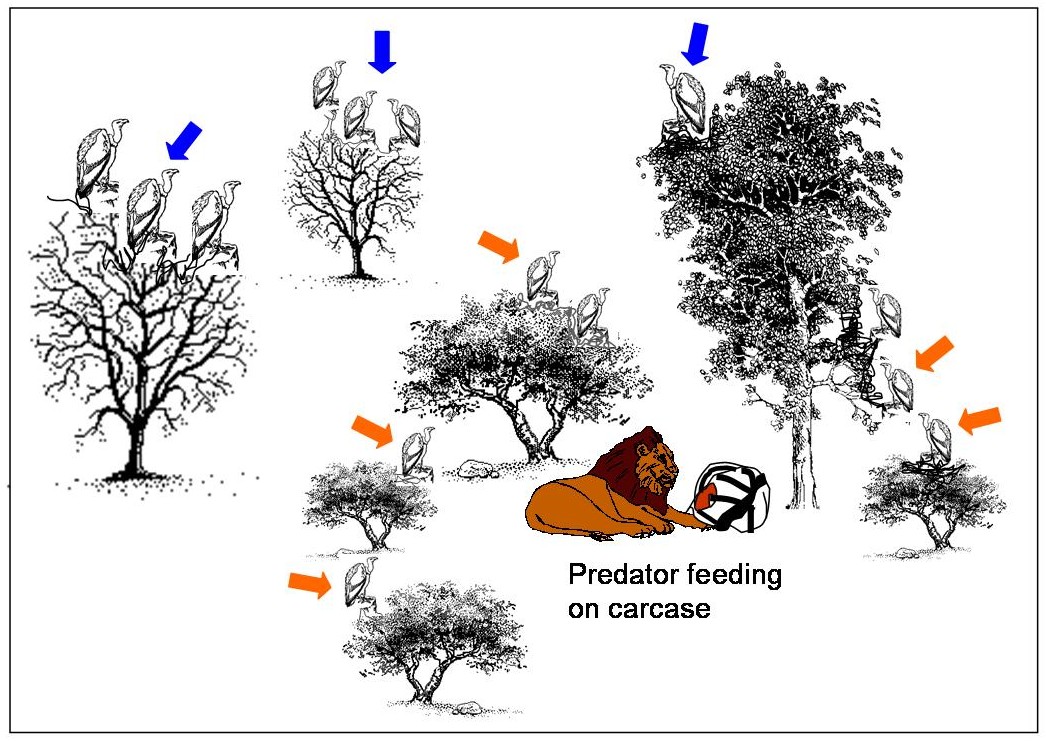

To understand vulture behaviour we must come to terms with the fact that vultures are opportunistic feeders that feed in a very competitive environment. Observe vultures on a kill. The competition is fierce with pecks and wing slaps being freely dealt out to both species of the same kind as well as other competitors. The bottom line is this. When vultures spot a carcass from a height (they have exceptionally good eyesight) they waste no time getting down onto the ground or surrounding vegetation if there are still large predators feeding. If you see vultures circling on thermals the only thing it tells you is that they are looking for food – not that they have found something.

If they do spot a potential meal they waste no time side-slipping and dropping as quickly from the sky as they can with legs extended and braced for a hard landing.

See Figure 4. If, as a vulture you snooze by hanging around in the sky too long when there is a meal to be had, you lose.

The next bit of useful information is to be aware of the fact that there is a feeding hierarchy at a carcass.

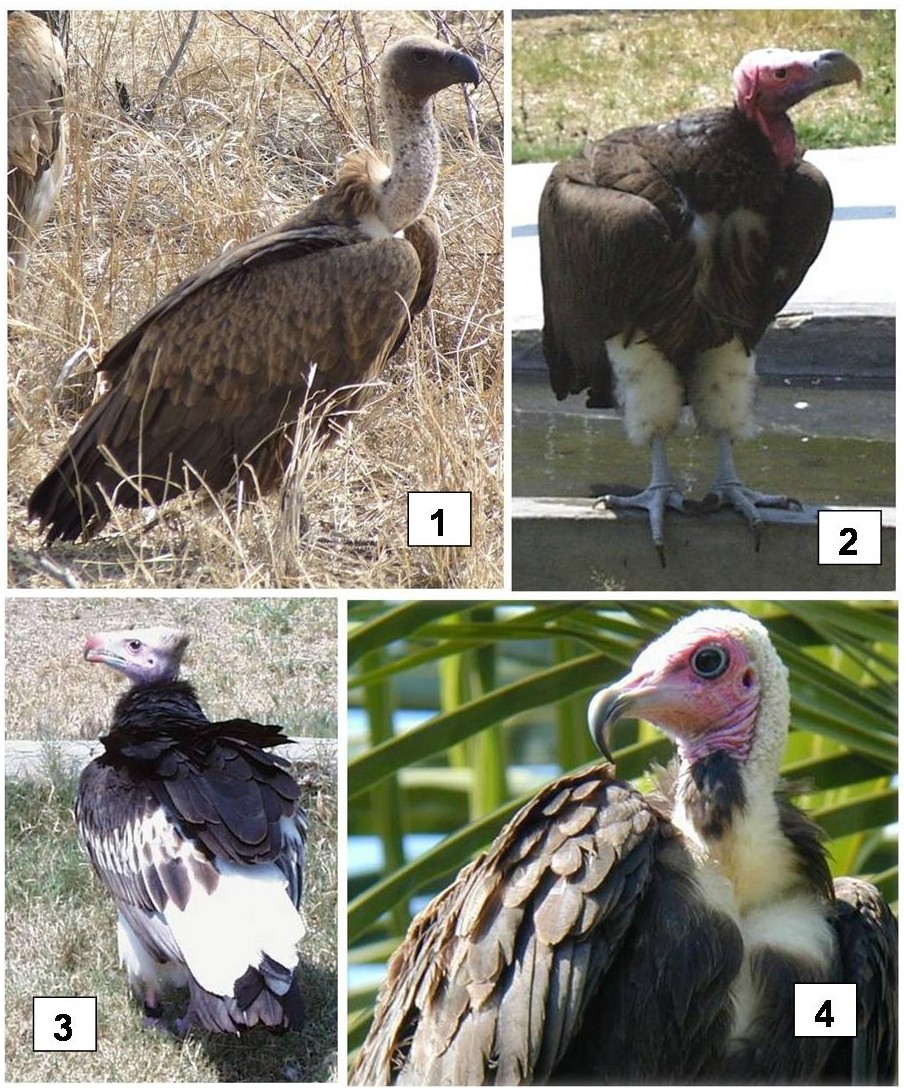

Some of the vulture species that compete at a carcass. Not shown is the Cape griffon which is very similar to the white-backed vulture and sometimes difficult to tell apart. A white-backed vulture (1), lappet-faced vulture (2), white-faced vulture (3), and hooded vulture (4) are shown.

As far as birds go there are about eight or nine species that compete for a potential meal. Of the vultures the Cape griffon (earlier known as the Cape vulture), the white-backed vulture, the lappet-faced vulture, the white-faced vulture, and hooded vulture are the main contenders. Giving them some competition are Marabou storks, Tawny, and bateleur eagles. Tawny and Bateleur eagles are often the first on the scene and will feed on the eyes and tongue of the dead animal.

The small hooded vultures will also try and get in a quick bite on soft parts before the large vultures such as the lappet face, white backed, white faced (quite rare in South Africa) and Cape griffon arrive on the scene to dominate the carcass. The eagles and hooded vultures have small beaks which cannot open a carcass and they are intimidated by the heavyweights when they arrive and fly off or hang around on the periphery to forage for scraps when the feeding frenzy commences. The large red faced lappet vultures with their powerful beaks are top of the pile – perhaps on a par with the long legged Marabou storks.

The lappet faced vulture is aggressive and opens a carcass with its large beak. This vulture and the long legged Marabou stork are dominant around a carcass followed closely by white backed vultures and Cape griffon. A timid hooded vulture can be seen hanging around on the periphery behind the stork.

They are followed a close second by white-backed vultures who are also usually the largest in number on a carcass and the less common Cape griffon. White-faced vultures are third in line with hooded vultures, eagles, and smaller raptors such as kites on the lower orders of rank.

The lappet-faced and white-backed vultures assisted by Cape griffon all possess powerful beaks with which they open up the carcass of even thick-skinned species such as buffalo.

This is when the fun begins as all the main contenders battle for the internal organs such as the heart, liver, lungs, spleen, kidneys, stomach, and intestines. Once this has been devoured they will turn their attention to the fleshy muscles of the shoulders, rump, and thighs. Occasionally some scraps or shreds of flesh may fly beyond the core feeding area and the hooded vultures will quickly dart in to eat the morsel before once again moving out of range of the larger species.

If, as a ranger, hunter, or guide you see vultures peeling quickly out of the sky you can be pretty sure that there is a dead animal in the vicinity.

If you approach the area where the kill is located and see a lot of vultures sitting in trees the chances are pretty good that there are large predators still feeding on the carcass. Be forewarned. Lion, leopards, and hyaena are intolerant of vultures and will chase them off until they themselves have had their fill to eat. Vultures and Marabou storks will then patiently wait perched on surrounding vegetation until the predators move off and will quickly descend when their turn arrives to feed.

Because the smaller hooded vultures have to nip in first to get at the tongue and eyes they will usually sit in lower branches close to the carcass. This can give an observer a good indication (especially in thick bush) as to where the carcass is lying. The larger vultures perch up higher and often quite a distance from the carcass. There is generally quite a lot of noise when vultures are feeding on a dead animal and the clucking, screeching, hissing and squawking of competing vultures can be heard a long way off under certain conditions.

If vultures suddenly flush up from the ground or move away from the carcass it is generally an indication that a large predator has arrived on the scene and is chasing the vultures off the kill. Vultures will feed on a carcass until just before sundown and will then roost in trees for the night.

Reading vulture behaviour can therefore be useful to hunters, guides and rangers.