Taking The Shot

With the understandable excitement experienced by first-time lion hunters shooting over bait under the low light shooting conditions of pre-sunset or pre-dawn or tracking lions on foot, which often culminates in a close-range confrontation.

It is no wonder that lions are wounded on occasion – a situation not to be taken lightly. The best way to avoid this is to make certain of the first shot.

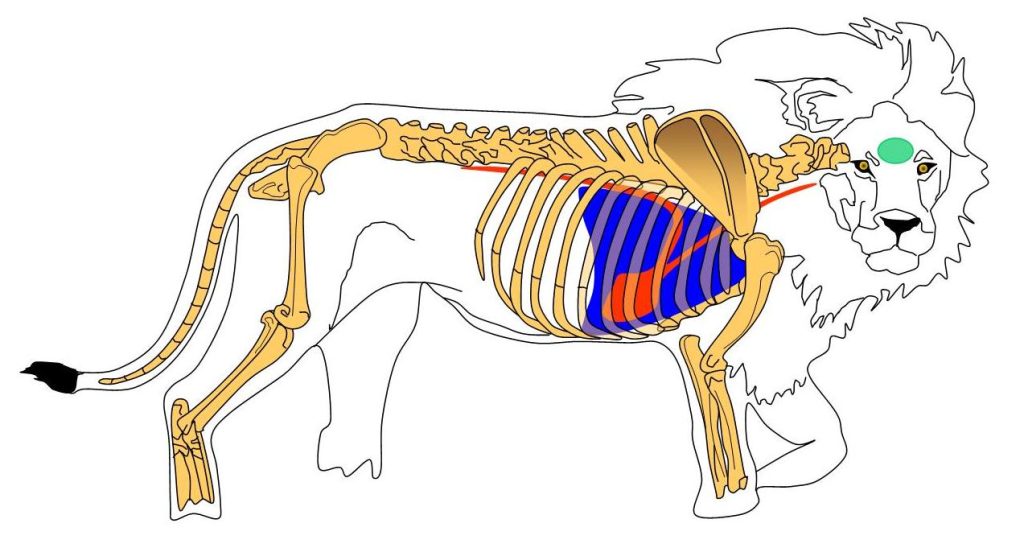

The most common shot taken at the lion is directed at the heart/lung area (see Figure 2).

From a side-on presentation, the heart lies quite far back, and from a frontal presentation, it is more or less in the centre of the chest (see Figure 3).

Lions are thin-skinned, relatively light-boned animals with tough muscles but are generally hunted with medium to large calibre, soft nose expanding bullets that are designed to “set up” (mushroom) quickly after entry to create a large wound channel. Although smaller calibres have been used successfully on lions, a calibre in the 7mm class delivering a minimum of 3,000 foot-pounds of energy should be regarded as the minimum.

After The Shot

A lion, if not killed immediately with a brain shot from a rifle, will usually react violently by growling fiercely, somersaulting, clawing, and often running off. This will be the same reaction on being hit by an arrow. If the shaft is visible, the lion may claw at it and bite it.

If possible try and get an anchoring shot in before it disappears from sight.

Following up on a wounded lion is a dangerous venture and should not be attempted without being accompanied by a competent professional hunter armed with a suitable calibre rifle. Do not attempt following up on an arrow-wounded lion with a bow. A wounded lion may go to ground and wait for followers to catch up whereupon they will carry out a determined charge. Many hunters have been mauled during hunts in Africa.

Follow Up

If the situation allows (enough daylight still left) wait 20 minutes before commencing with a follow-up. This will give enough time for the animal to bleed out and die or succumb to its wounds from the trauma inflicted by a bullet or arrow. Following up too soon may also induce further flight.

The initial shot will of course influence what follows. Often a good heart/lung shot will not have an immediate effect and the animal may run off and expire shortly. As you follow up on what you may initially have thought to have been a wounded animal may prove to be a dead one and the problem is resolved. If, however, the lion has indeed been wounded you can be reasonably sure of one thing and that is if you find it, and it is still alive and sees you, it will (eventually) charge. It may run off the first time it becomes aware of your approach but if pursuit continues the lion, will at some point, make a stand. Depending on vegetation density a charge may occur from very close or may even be initiated at a distance of up to 100 meters – a distance covered by a charging lion in 3.5 – 4 seconds, affording you very little time to get in a killing shot.

When setting out to find a wounded lion make sure you have a calibre that can deliver enough stopping power using well-constructed soft-nosed bullets in the 300-500 grain class. A double rifle would be an advantage that would afford you the luxury of a quick follow-up shot should the first one miss or fail to stop a charge. A bolt action rifle can also be used but may, in the short space of time available, not be able to be cycled quickly enough for a second shot.

As you set off on the trail of a wounded lion, you will be looking for a possible blood trail. (Figure 4 and for tracks (see Figure 5).

Sometimes possible scat can be found as injured animals will sometimes evacuate their bowels. The scat is dark and very smelly and depending on where the animal has been wounded may contain traces of blood. Keep the wind in your favour and your rifle held at the ready with a round chambered – if you unexpectedly walk into the lion or are charged – you may not have the time to chamber a round.

Proceed slowly and with caution. Be on the lookout for other animals running from the lion or warning of its presence with snorts or alarm calls. Also, keep your ears open for growling as this will often precede a charge.

In areas of limited visibility carefully search out areas ahead and look “through” instead of at vegetation.

Approach thickets with caution as lions will often hide up in these areas, watch their back trail, and may suddenly with a disconcerting growl charge with the intent to kill and you don’t want to end up in the claws of an enraged feline of the Panthera leo species.

The distance a lion may move from the place where it was initially wounded will depend on several factors – the severity of the wound, the type of wound, whether or not bones have been broken, the amount of blood loss, and so on. A lightly wounded lion may cover a substantial distance in a short period.

When a wounded lion becomes aware of being followed it can cause it to increase its efforts to escape (i.e. put in more distance between themselves and the pursuer/s) or may decide to make a stand.

If possible, it is better to get a second or subsequent shot in at a lion lying down, standing still, or walking away from you as this may afford you more time to take a carefully aimed shot as opposed to taking a snapshot at a lion that is running.

For side-on shots, the best option would be to again target the heart/lung area. The brain is too small a target for a broadside shot which will destroy the skull (the trophy) and as the lion is facing away from you and poses no immediate threat to your life, is not really justified.

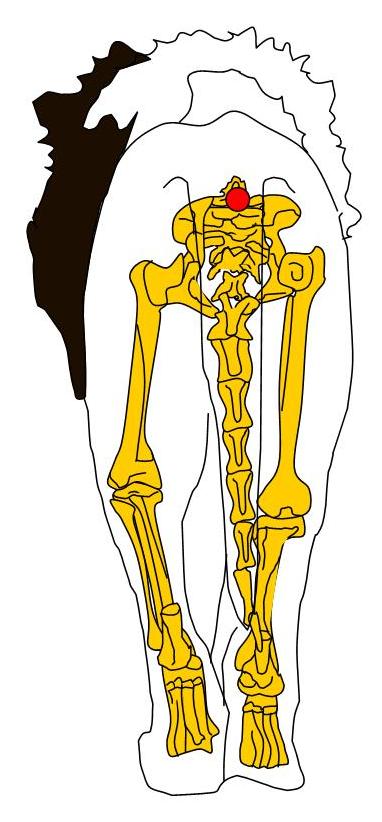

Breaking the shoulder from a broadside presentation is also not recommended as lions can run off with such an injury and still do you harm at a later stage. If the wounded lion is heading directly away from you a shot may be placed just above the root of the tail to break the spine (see Figure 8) and “anchor” the animal.

The term anchor may turn out to be relative as a lion may drag itself forward using its powerful forequarters and legs. It will however be slowed down enough to afford you the opportunity to get a killing shot in.

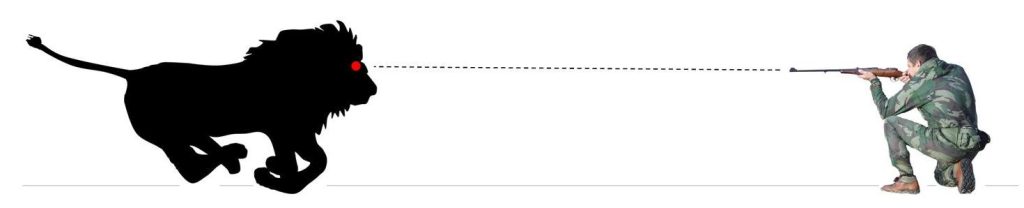

If you are faced with a real charge – that is, by a lion running as fast as its condition may allow (which may be a whole lot faster than you would comfortably like!) – you have two options, and here you may find that not all hunters will agree. You can elect to go for a brain shot. A very difficult shot at best – the head will be moving, and the target you will be aiming at will be small – only about 5-6 cm frontal cross-section.

If you do hit the brain however it will put the lion down immediately and permanently. Some hunters do not feel comfortable with this shot because of the small, moving target that must be hit and because the sloping bones of the skull may deflect a shot off course. Many hunters prefer to go for the frontal chest shot which offers a far greater target area (see Figure 3).

If a bullet of adequate calibre and construction is placed squarely in the centre of the chest it will usually drop a lion but if the shot is slightly off target it may fail to stop the lion and it is then likely to inflict some serious damage, or worse, to the hunter.

Additional advice that may prove to be beneficial is to not shoot too soon at a charging lion. In all likelihood, you may only get one shot in (especially using a bolt action rifle) so make sure of the first shot. A lion will often warn you of an impending charge by growling and lashing the tail side to side. In non-wounded lions, this may be followed by a short rush and then stopping with the body held close to the ground.

Growling may continue and if the person being charged does not back off slowly (always facing the lion) a second short rush may follow. If the person continues backing off the lion may then turn and trot off. A charge may only possibly be carried out to a conclusion if the person does not back off but just standing ground may also at times be enough to cause a lion to back off.

A wounded lion is a different story. If a charge is initiated it will usually be carried out to completion and the only way to bring it to a stop is to kill the animal. Because lions adopt a low posture when charging it is sometimes easier for the hunter to place an accurate shot by going down on one knee so that the axis of the bore falls into the same plane of the target being aimed at instead of aiming down at it.

As a rule, keep shooting whilst you have the time and ammunition until the lion stays down. When you think the animal is dead make sure you have another round chambered and observe it for a few more minutes longer before approaching to confirm death by getting no response from the corneal reflex.

After the euphoria of the moment when the demise of the lion has been confirmed please don’t forget to unload all weapons and make them safe.