Greater kudu, nohngo, mbizi, Tragelaphus strepsiceros, or by whichever name you wish to call it, this species is without a doubt one of Africa’s most beautiful antelopes. Even the females who do not carry horns are elegant, long limbed, aristocratic – garbed in dove grey and white stripes – they are a joy to behold. The males with their expansive spiral horns are elegant and kingly, and most hunters are unashamedly covetous of these trophies.

The kudu is a large, slender antelope weighing between 150–250kg (males) and 120–210kg (females). The body colour is greyish brown to rufous. Six to ten vertical white stripes descend on either side of the body, from the dorsal crest. The head is darker with a white chevron between the eyes and three white spots on the cheek, below the eye. A fringe of hair extends from the chin to the neck. Muzzle and lips are white. The tail is short and bushy with a white underside and black tip. Horns, found generally only in males (rarely in females), are long and diverging, spreading in 2–3 open spirals.

Greater kudu have a wide distribution and are to be found in Botswana, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique south of the Zambezi River and in South Africa, where they occur in the North West Province, Northern Province, Mpumalanga, Swaziland, north eastern KwaZulu-Natal.

Kudus prefer savanna woodland and are partial to areas of broken, rocky, or hilly terrain, usually in fairly close proximity to a source of water. They will often also be found in riverine habitats. In arid country, they are confined to Acacia woodland, Terminalia thickets on the fringes of watercourses, or in bush tall enough to provide cover (See Figures 1 and 2).

Kudus are not usually found in open grassland except when crossing it to other suitable habitats.

Kudus are gregarious, occurring in small herds of 4–5 but seldom more than 11. Herd size appears to peak during November to January (just prior to calving) and again between June – July during the breeding season. Adult bulls are usually associated with female herds but can be found alone or in small herds of up to six, between August to May. Kudus are mainly active in the early morning or late afternoon. They rest up in dense cover or woodland during the heat of the day.

In areas where they are harassed, they may become nocturnal in their habits. They are shy antelopes, always alert and cautious. They will take a few steps at a time, then stop, look, and listen with large, radar-like ears pivoting this way and that, nostrils flared and quivering, testing the air (see Figure 3).

If suspicious or disturbed in open areas, they will immediately take flight to the nearest cover, tails raised, white and fluffy in warning and indicating the direction of flight to those following. Once spooked, they will seldom look back or stop to determine the cause of their fright. They are less nervous when standing in dense cover and will often “freeze” whilst observing an intruder. When standing still, they can blend in superbly with their surroundings, making them very difficult to spot. Kudus are accomplished jumpers and clear a 2m high fence with consummate ease. When alarmed, they emit a loud, hoarse bark which is deeper than a similar sound made by bushbuck.

Kudus are predominantly browsers (see Figures 4 and 5) and utilize a wider range of species than other antelopes. They prefer leaves and young shoots but will also eat seedpods such as Acacia tortillus (hak-en-steek), leaves of Aloe species, and other plants that are poisonous (e.g., Solanum spp.) or avoided by other browsers. Kudu prefer forbs to woody plants. Kudu will drink day or night and require about 9 litres of water a day (see Figure 6).

Most calves are born between January to March, but can also be born at other times of the year. The breeding season is June to July. Gestation is 210 days, after which a single calf weighing 15–17kg is born. Calves are born after midsummer when grass is at its tallest. Cows leave the herds to give birth, taking cover in long grass. The calf will be hidden in the long grass for a few days after birth until it is strong enough to travel with the mother.

HUNTING THE KUDU

Trophy

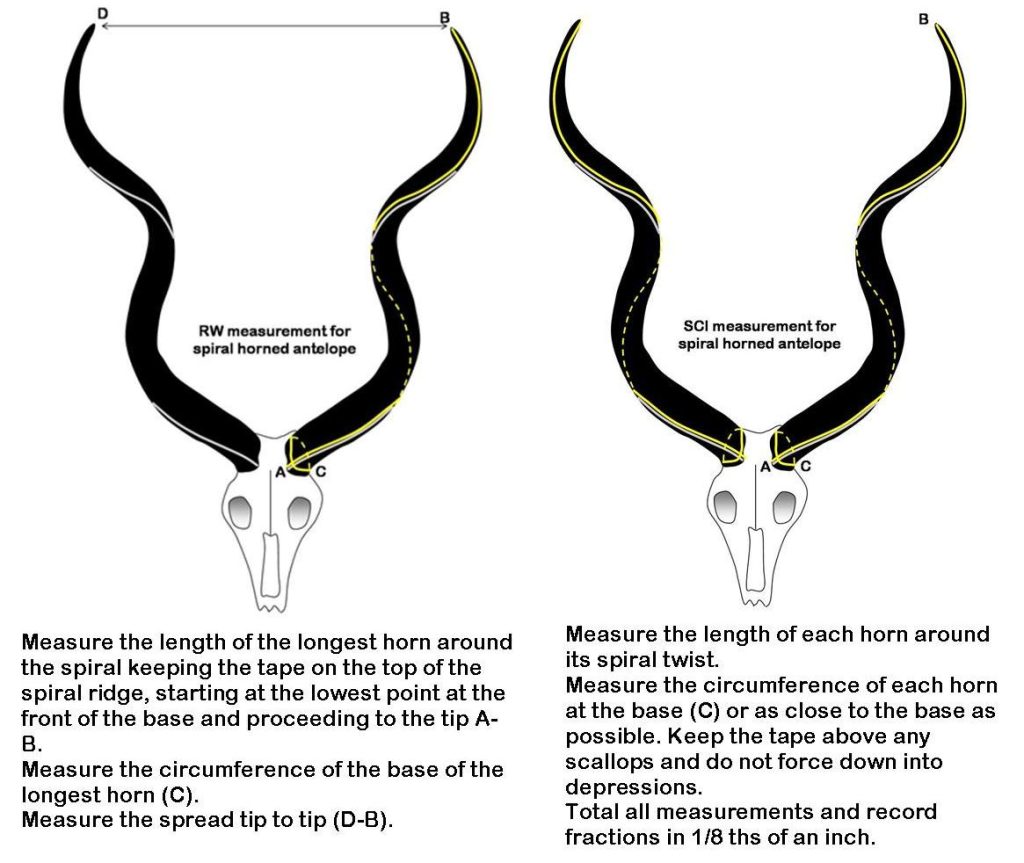

The first turns of the spiral horns are completed at about the age of 21 months, and the second at about 30 months. The horns grow throughout life and begin their third turn at about the age of 8 years. A bull with three turns is generally past breeding prime. If you are looking for record book trophy horns, the minimum for Rowland Ward recognition is 537/8 “ (137cm) or an SCI score of 121. The methods of measurement are shown in Figure 7.

Signs to look for

Apart from visual sighting, the bowhunter can be alert to other signs which will indicate the presence of kudu.

Spoor

The hoof is cloven, typically oval in shape, and 55–80mm long. The forefeet of the males are relatively broader than those of the females. (See Figures 8 and 9.)

Scats

Dung pellets are usually about 20mm in length, slightly shorter and narrower than eland and giraffe but larger than impala. Accumulation of pellets may be found in favorite feeding spots. (See Figure 10.)

Debarking

During periods of shortage, kudu will use bark as a source of food, using the incisors of the lower jaw to scrape it off.

Horning

Kudu bulls use their horns to break off branches to gain access to leaves normally out of reach. Ground-horning, when the horns and face are rubbed in mud or dry ground, is a form of territorial behaviour found in kudu as well as in nyala, bushbuck, and wildebeest.

Browse lines

In areas where there are large populations of kudu and /or other browsers a distinct “browse line” becomes evident in the tree foliage. This is the vertical distance from ground level to which animals can extend their necks to reach and utilize food.

Vocal sign

The bowhunter must listen for the guttural alarm bark of kudu as an indication of their whereabouts.

Hunting techniques

Concentrate your efforts in the typical habitat and look for relevant signs. It is usually easier to hunt lone bulls. When they are associating with breeding herds or other bulls, there are more collective senses to monitor their surroundings. The best hunting techniques are those that require the animal to come to you whilst you wait in ambush. Stalking up to within bow range of a kudu on foot is not impossible, but it is not easy. The hunter must be well camouflaged, always stay downwind, move slowly, and stop often. Due to the fact that kudu often frequent hilly terrain, one technique (spot and stalk), involves sitting on a high vantage point and glassing a wide area.

Once kudu are spotted, a careful stalk can be planned. A thorough reconnaissance of an area will sometimes give you a good idea of where kudu are likely to be found. Signs such as fresh and abundant spoor and scat along well-utilized game paths (especially in the vicinity of a waterhole) are promising indications, and hunting from a stand, platform, or hide then becomes a viable option. Find suitable cover or erect a blind/tree stand downwind and within 10–25m of your expected ambush point. Wait patiently, immobile and quiet. If a kudu approaches, exercise restraint and wait until the correct shot presents itself before loosing off an arrow.

Walk-and-stalk techniques can be successfully employed in dense bush or woodland, provided the hunter does more observing and waiting in good cover than walking or moving about. (See Figure 11.)

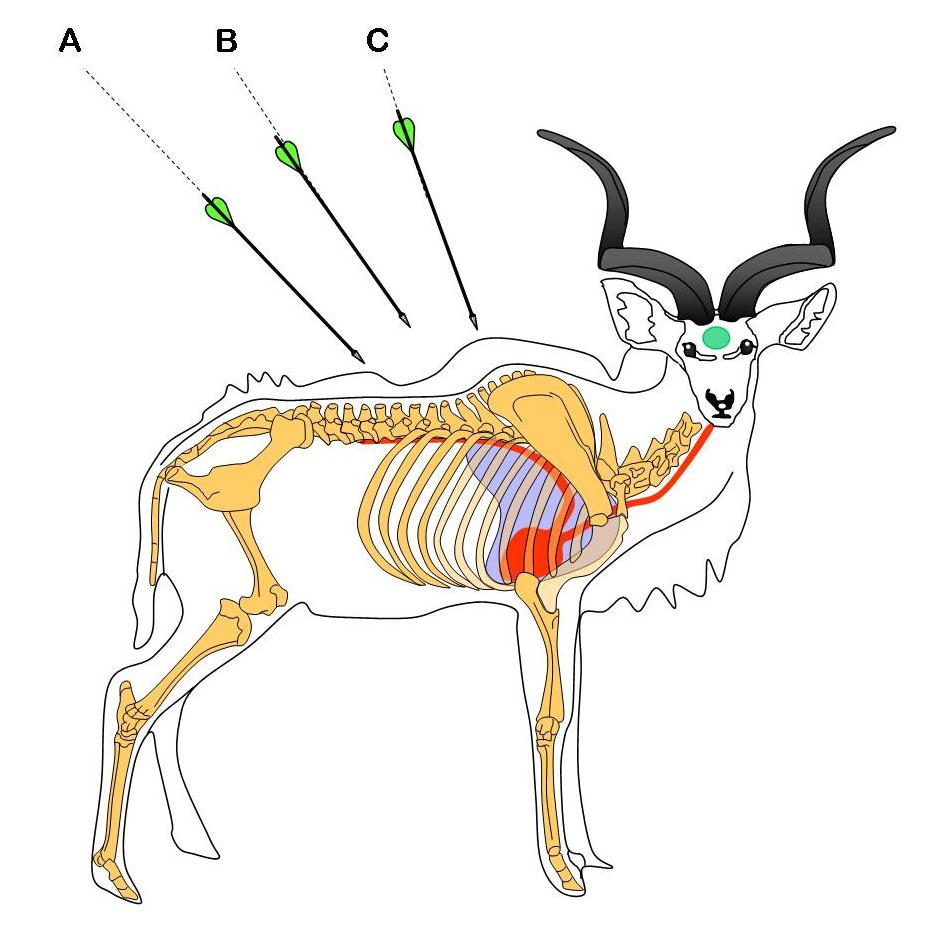

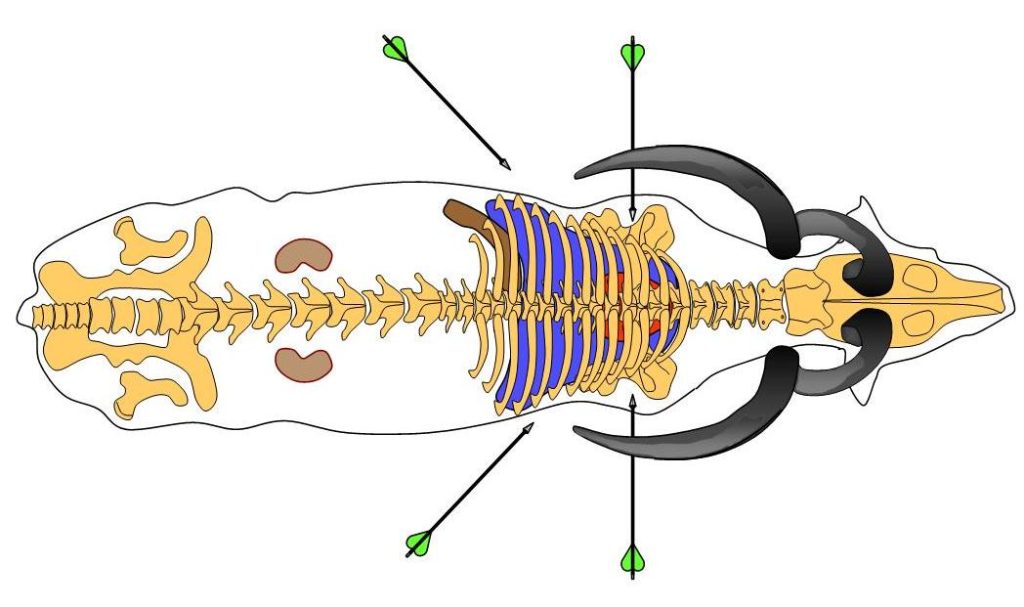

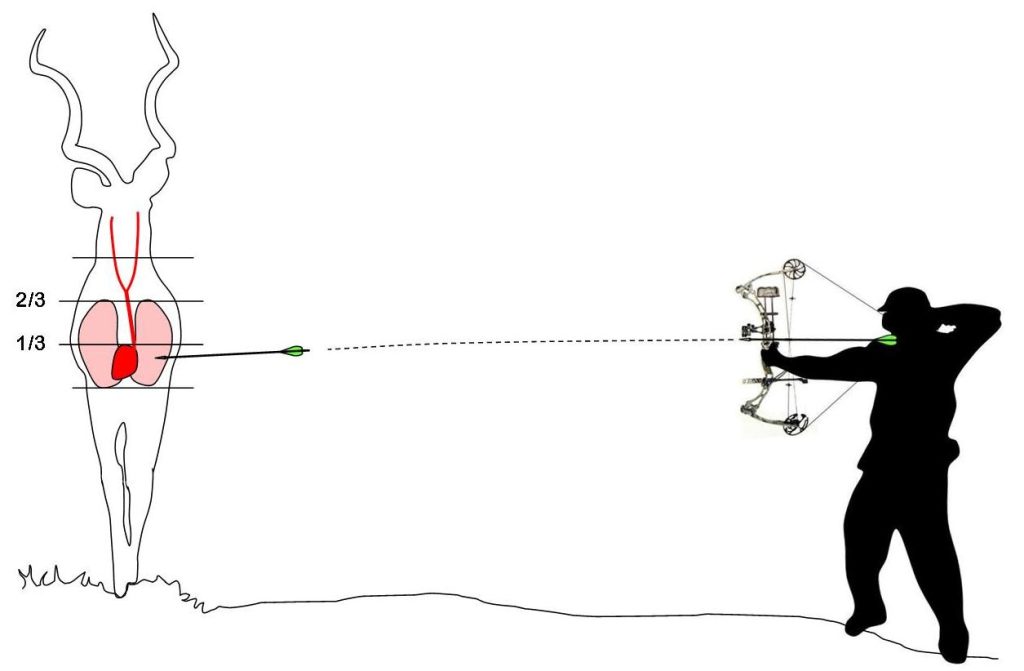

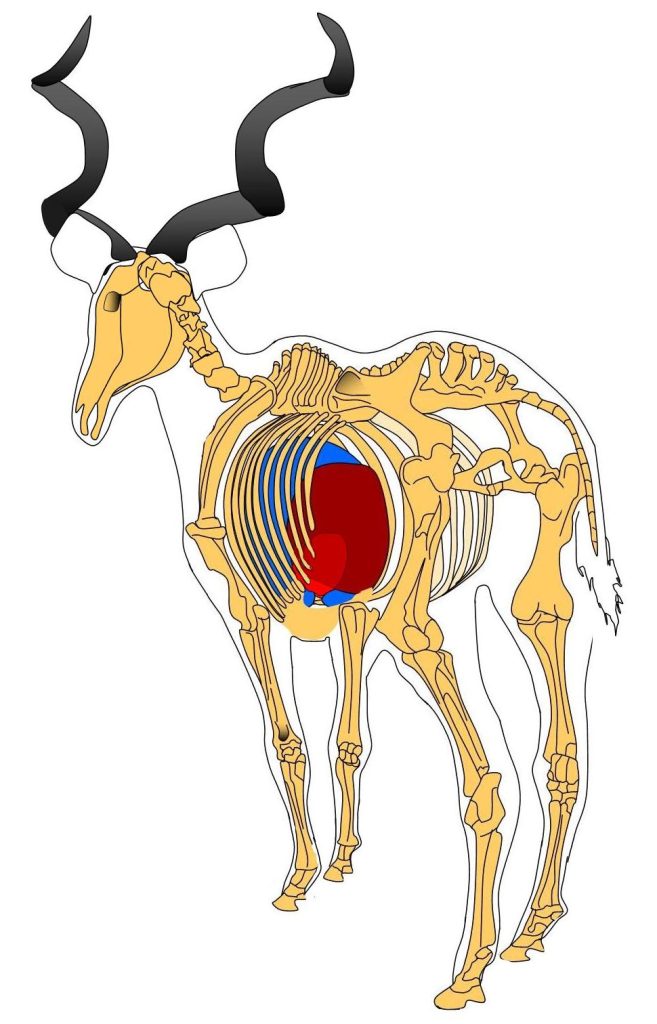

Shot placement (See Figures 12 to 15).

There are three acceptable shots for kudu with bowhunting equipment. The broadside heart/lung shot is the safest and one that offers the greatest margin of error for shot placement. A well-placed arrow will cause maximum hemorrhage, double lung collapse, and rapid death. A quartering away shot with the arrow entering between the ribs and pelvis is very effective and will penetrate the liver (likely), spleen (possibly), diaphragm, lungs (one or perhaps both), heart, major blood vessels, and gut. Organs involved along the wound channel will depend on which side the quartering away shot is taken. The hunter must aim for the opposite front leg at the right elevation.

A third possibility, which can be a little tricky, is from an elevated hide or stand. Here, the hunter must aim slightly back (with the animal facing away) and next to the spine so that the arrow is angled forward to end up in the vitals. The angle at which the shaft must enter to end up in the vitals and the external aiming point will depend on the position of the hunter in his elevated stand, relative to the animal.

Do not attempt shots when the animal is looking at you. Shoot only when the animal is looking away or its vision is obscured. Do not attempt frontal, quartering on, or tail-end shots.

Arrows generally penetrate easily into kudu with quartering away shots and frequently pass right through on broadside shots. Kudus are slender animals and do not have much breadth across the chest. Ribs are not very thick, and arrows pass through them with relative ease. Kudu are not very tough and will go down quickly with a well-placed heart/lung shot. They have a total blood volume of approximately 14-16 litres and will die if they lose one-third of this volume. When hit, a kudu will bound off and head for the nearest cover. Wait at least 30 minutes before following up.

A bow of 60-75 pounds draw weight is recommended for shooting arrows of 500 grains plus, delivering a kinetic energy of 60-70 foot pounds and a momentum of 0.4 slugs or more. There is a wide variety of two and three-blade broadheads and mechanical broadheads available, which will work well on kudu.