Having recently completed a free-lance safari for a local hunter/landowner in the Gwaai Valley, I was spending my ‘down time’ with my good friend Stuart Campbell on his Lion Ranch. He asked me to travel to Hwange town to collect some extra groceries, in preparation for the imminent arrival of a small group of South African visitors. Late that afternoon the guests arrived, and one of them, an Air Steward with South African Airways expressed his eagerness to ‘shoot something’.

Understandably, Stuart regarded the game on his ranch as a business asset but agreed that this fellow, we shall call him ‘Johan’, could shoot one of the numerous impalas, or perhaps a warthog, to satisfy his bloodlust. (The staff would welcome the unexpected extra meat, and Stuart’s kitchen too needed some venison.)

Standard practice with overseas hunters involves quizzing them subtly, during the journey to the area of operations, to gauge their knowledge and experience, before assessing their musketry skills while conducting a ‘zeroing’ session. With perhaps an hour of daylight remaining, there was little time for such niceties, so I accompanied him to the gun cabinet containing both Stuart and my rifles, to choose the tool with which to do the deed.

Of medium build, Johan was around my height. Dressed for the occasion, he wore designer khaki, sensible-looking boots, and a tidy camouflage bandana. His thick-framed black spectacles detracted somewhat from the otherwise ‘Croc Dundee’ image, although he never carried the ludicrously huge hunting knife of that dubious Australian dude.

When his hand settled on my beloved walnut stocked, Walther .375 H&H Magnum, (he knew a superior firearm when he saw one), I enquired about his experience with heavier caliber rifles. The excited resume´ that followed included such weaponry as the ubiquitous .458, a .416 double, and an aging .404 Jeffry. Reminding him that the rifle he selected sported a wide-angle, variable-power telescopic sight, he scoffed at my concerns about the man-sized shock of the recoil from the unusually light weapon. It kicked like a malignant Serengeti zebra.

Shooting light was failing fast and after doling out some precious, expensive ammunition, we jumped into the Land Cruiser and headed off towards the Gwaai Valley flood plain where I predicted the openness of the terrain would offer the best chance of a late afternoon shot. Stopping short of the open ground, I led him through the light bush towards the river.

Carefully approaching the vast corn-colored grassy glade, we espied a solitary male warthog foraging for roots, perhaps a hundred yards away. With one broken tusk, it had no value as a trophy. Beckoning Johan forward to a vantage point with a good field of fire, I noted he opted for a sitting shot – perfectly viable in the circumstances, although knowing the rifle as well as I did, not the posture I would have chosen. Focusing my pocket-sized binoculars on the oblivious warthog, I waited for the shot.

Following the titanic bang, I observed the strike of the shot, and without taking the glasses from my eyes, I announced his clean miss – high, and to the right and, since he was not a ‘paying client’, commented wryly that the warthog was the safest on the planet. Not hearing the sarcastic rejoinder I expected, I turned to look at my companion.

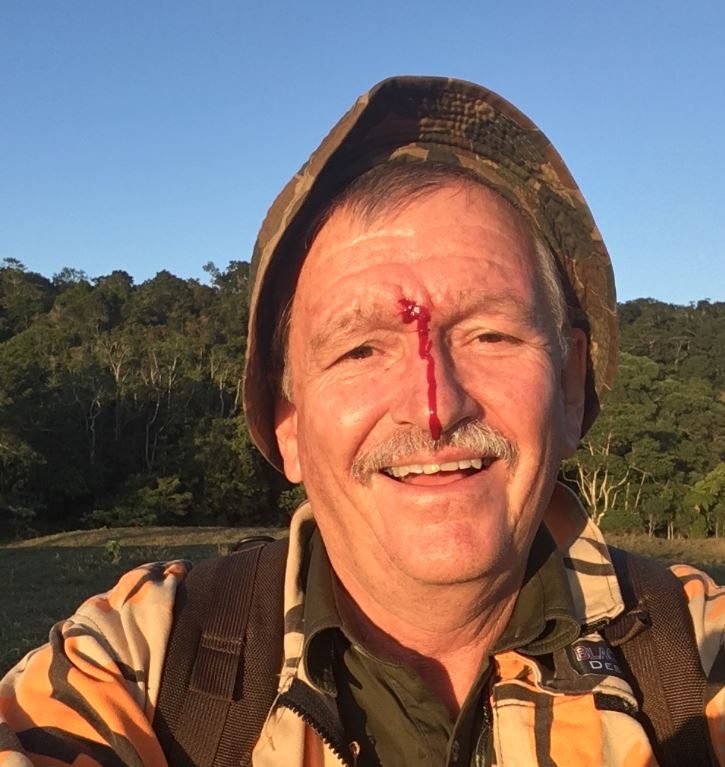

The rifle lay safely in the cradle of his lap, and his shattered Woody Allen glasses lay on the Kalahari sand beside him. With his hands covering his right eye, I watched the bright blood escaping from between his partially splayed fingers. Relieving him of my precious firearm, I helped him to his feet and took the bandana from around his neck to hold against the pumping eye socket. Worried that glass from the devastated spectacles may have entered the eye when we reached the vehicle, I stood over him, holding the eye open as widely as possible I poured the entire contents of my water bottle into the ravaged socket.

At the end of the Rhodesian bush war, the owner of the nearby Gwaai River Hotel employed a former Warrant Officer in the Medical Corps and his nurse-trained wife as managers. They had been of invaluable assistance when a skinner slipped with a knife, or some other hazard of the profession took its toll. With Johan holding the makeshift dressing to his eye, we drove in stoic silence to seek the expert medical assistance of Sergeant Major Jock Pirrie (retired).

“He looks a bit like Henry Cooper did after that 13th round,” Jock offered, likening the bleeding to the famed British boxer’s epic battle with a youthful Cassius Clay years before.

Expertly stitching the wrecked socket together and administering a tetanus shot, Jock commented sardonically, “That has to be the best example of a ‘Weatherby Kiss’ I’ve ever seen!”

Me too.