What do Pyramid Schemes and intensively breeding and manipulating new wildlife colour variants and other unnatural freakish animals have in common with one another? Pyramid Schemes are defined by Wikipedia as, “an unsustainable business model that involves promising participants payment or services, primarily for enrolling other people into the scheme, rather than supplying any real investment or sale of products or services to the public.”

They go on to add, “A successful pyramid scheme combines a fake yet seemingly credible business with a simple-to-understand yet sophisticated-sounding money-making formula which is used for profit … The flaw is that there is no end benefit. The money simply travels up the chain. Only the originator and a very few at the top levels of the pyramid make significant amounts of money. The amounts dwindle steeply down the pyramid slopes. Individuals at the bottom of the pyramid (those who subscribed to the plan but were not able to recruit any followers themselves) end up with substantial losses.”

It’s best not to get involved in plans where the money you make is based primarily on the number of distributors you recruit and your sales to them, rather than on your sales to people outside the plan who intend to use the products”

The wildlife game ranching industry in South Africa where genetic manipulation was used to breed colour variants (Figure 1) and animals carrying abnormally large trophies (horns) was always destined to fail. All pyramid schemes eventually collapse.

From early at the turn of the century this industry saw phenomenal growth and by 2014 colour variants and genetically engineered trophy animals were selling within the industry at unimaginably inflated prices. Those involved in the scheme must not now say that they were not warned at the time by myself and others such as renowned hunter and conservationist Peter Flack. Perhaps it is because there are some who understand the heart of the true hunter and knew deep down that no true hunter would take delight in hunting a genetically engineered freak – especially at exorbitant prices or that it would be an accepted practice condoned by internationally renowned hunting organizations.

And here it is important that we must draw a clear distinction between “traditional” game ranching and “genetic” game ranching. I stand 100% behind game ranching in the traditional sense where wildlife was “farmed” instead of or in combination with domestic livestock for the express purposes of producing venison and for hunting. Ecotourism was also factored into the equation and it was a successful formula. I believe the private “traditional” game ranching industry in South Africa prior to the genetical engineering saga did more for conservation in Africa than all the official conservation agencies combined. Credit must be given where credit is due. But things started to go horribly wrong and resulted in a negative “backlash” on the hunting and game ranching industries when certain individuals, in the interests of making “potloads” of money, started captive lion breeding programs and actively breeding strange colour variants by using intrusive genetic engineering techniques. They believed that hunters would queue up to hunt wild animals of abnormal colour and animals carrying massive genetically manipulated trophies. They miscalculated – big time. But they can never say that they were not warned that it was an unrealistic, unsustainable and unethical project.

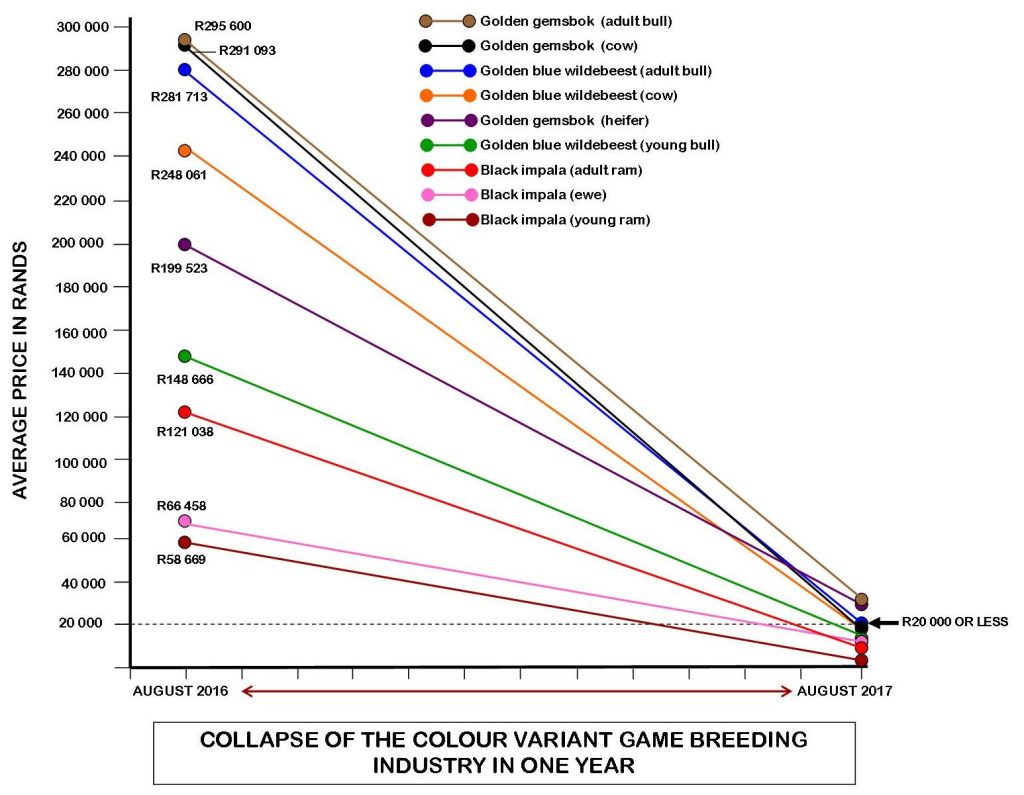

Just how big was the crash in this industry? Figures published in the November 2017 issue of Game and Hunt (Wild & Jag) tell the story and it is scary – especially if you were one of those who invested huge amounts of money in buying and breeding colour aberrations. Yes the originators of the scheme may have made a “quick buck” before sanity finally began to prevail but those who climbed onto the bandwagon at a later stage were taken for the proverbial ride and lost substantial amounts of money.

Figure 2 shows how the prices of some colour variants plummeted between Aogust 2016 – August 2017.

The colour variant game breeders can argue whichever way they will – the figures tell the story.

They proposed that the only way for breeders and manipulators to make money over the long term was to persuade hunters to pay exorbitant sums of money to “hunt” these abnormal animals. They were thankfully very unsuccessful and it would seem that most, if not all, of the sales transacted were from one breeder to another at ever-increasing prices. In other words, the sales were not “to people outside the plan who were intended to use the products.”

It was a conservation and ethical disaster and I doubt whether we will ever see a resurrection of this particular facet of game ranching. For this, I will shed no tears. Acclaimed international hunting and conservation bodies were quick to expose this scheme and passed recommendations in which they opposed “artificial and unnatural manipulations of wildlife including the enhancement or alteration of a species’ genetic characteristics (e.g. pelage colour, body size, horn or antler size)”.

This was a shameful and embarrassing blemish on the South African game ranching industry which before the colour variant debacle, had such a proud history of ethical conservation and sustainable wildlife management and utilization in the hands of the private landowner. Let’s learn from this lesson. A very important aspect which has not even been mentioned in this article is the whole ethical dilemma of “messing” with wildlife genetics and the far reaching effects it could have on wildlife populations. This is an issue deserving of a whole article in and of itself.

With South Africa in the throes of recession, downgraded to junk status, and with drought, avian flu, and other maladies threatening food security it may be the right time to return to traditional game ranching. It will be easier to justify this type of land use to a government intent on expropriating land than trying to justify ranching with colour variants for an end user that does not exist. Or at least in the numbers that colour variant game breeders had hoped for – i.e. hunters prepared to pay extravagant amounts of money to shoot genetically engineered freaks. There is little point in harping on the issue. Let’s learn from our mistakes and get back to what game ranching/farming was originally intended to be – providing healthy food (venison) (Figure 3-5), allowing animals to breed naturally, and hunting “normal” animals that have not been genetically manipulated(Figure 6).

This still has huge potential – not only in South Africa but in Africa at large – if Africans can be made to understand this (Figure 7).

It contributes significantly towards conservation and is sustainable. South Africans are leaders in the field of game ranching and could become actively involved in the rest of Africa by providing the necessary expertise. It can also go a long way in helping to work towards the continents’ future food security and create job opportunities.