“The charge of a wounded buffalo does not faze them too much. Give them the snarl of an angry lion in the Mopani and they can deal with it. They know what to do with the grey avalanche of an Elephant charge.”

But when a professional hunter finds a black mamba in a hide or one stands up at face level next to a trail with its neck flattened in a narrow hood, the bravest of Africa’s hunters become – what is the right word- extremely careful. No, let me just say it – they get scared.

And well they should.

Through the ages, the black mamba has been respected and feared by Africans of every colour. A bite from a large black mamba can cause death within 7-15 hours. The venom attacks the nervous system and the victim, fully conscious but with all muscles paralyzed, dies from respiratory failure.

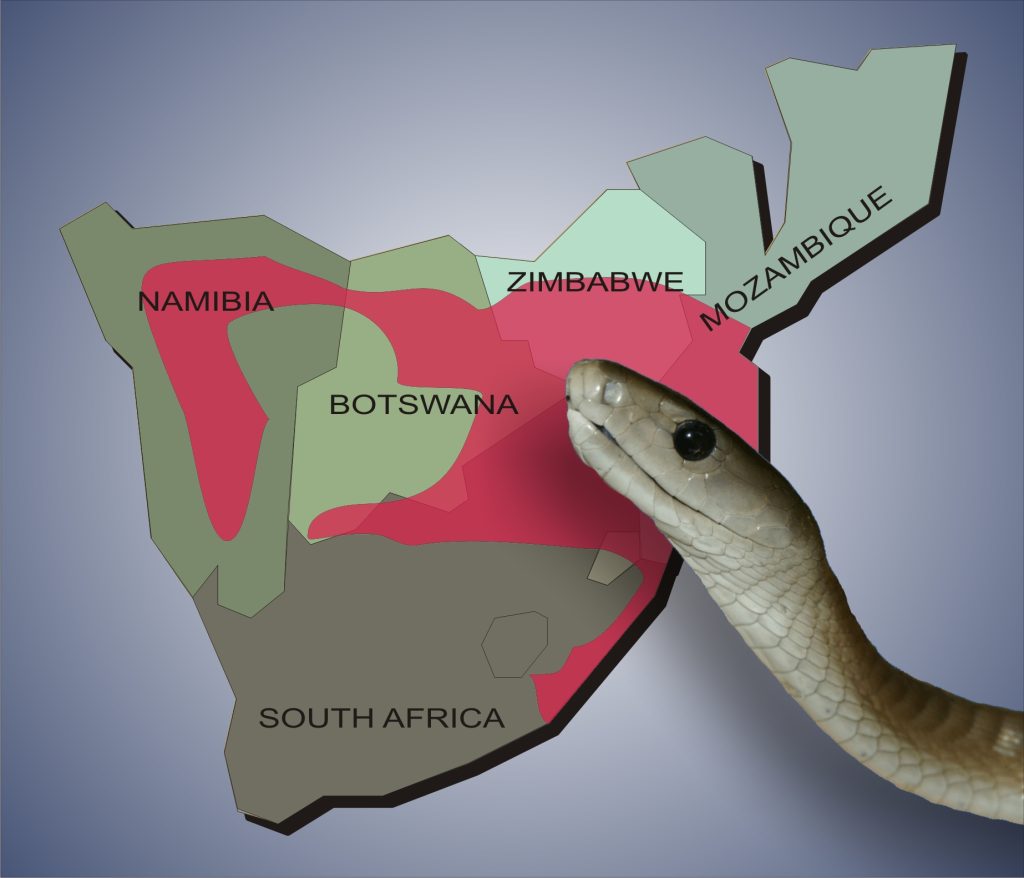

Africa’s largest poisonous snake, they can grow to lengths of 4.3 meters (14 feet). It has a streamlined body with a coffin-shaped head. The back is uniform gun-metal gray to olive brown, never black. The Black Mamba is named not for its skin colour, but because the inside of the mouth is black.

The belly is pale green, sometimes with dark blotches.

Behavior

A graceful, alert, and unpredictable reptile, this deadly poisonous snake hunts for its food during the day. Hunting is done from a permanent lair (usually termite mounds, mammal burrows, and rocky outcrops) to which it will return regularly.

It normally attempts to escape when approached, but if cornered will bite readily and numerous times. When threatened, the black mamba lifts the front third of the body and displays a narrow hood, gaping the mouth and showing the black inside of the mouth. A large mamba can raise itself up to face level.

It also hisses as a threat but will retreat if you back off. Only the very foolish do not – and the Black Mamba will lift two-thirds of it’s body off the ground when the strike happens.

Three black mambas, each about 2,5 meters long were occupying a heap of large creeper-covered boulders on the Limpopo river bank. Sugar birds would hover near the creeper, virtually motionless despite their whirring wings as they gathered nectar, pursuing one another in swift, darting flight, seemingly unaware of the snakes.

Every once in a while one of the birds would fly too close and be snapped up, fluttering desperately as the deadly poison took a quick toll on its victim. The bird’s struggle lasted a few minutes before it hung loosely in the snake’s jaws. Sometimes the birds were swallowed immediately but frequently the mamba released its grip, placed its prey on the rock, and inspected it with a flicking tongue before starting the meal.

A change of diet was provided by a rock rabbit that ventured too close. No sooner had it squatted down to scratch itself than one of the mambas slid from under the creeper, and delivered a quick bite, instantly releasing its grip to await the effect of the venom.

The rock rabbit scuttled back to the crevice energetically as if it had not received a fatal dose, but the mamba waited with supreme confidence. After a few minutes, it slid after its victim, dragged it from the crevice, checked to ensure that it was dead then grabbed its head and started eating.

The Venom

Neurotoxic venom is powerful, usually proving fatal if first aid treatment is inadequate or if antivenin injections are delayed too long. A large snake can yield about 200-300mg of venom or more. 10-15mg is usually fatal for humans, so a single bite can kill ten grown men. Large volumes of antivenin are required, usually up to 10 ampules to counteract the venom.

The neurotoxic venom interferes with the impulse transfer from nerve endings to skeletal muscles leading to paralysis. The signs and symptoms can escalate rapidly from a feeling of numbness around the mouth, to sweating, drooping eyelids, a drop in blood pressure, inability to keep the head upright, difficulty in walking, difficulty in swallowing (saliva running from the mouth) to where the patient stops breathing – and eventually without medical intervention, this will lead to death.

Treatment

Within a few minutes from a mamba bite, there is numbness around the mouth that progresses to relentless widespread muscle weakness leading to respiratory failure in 60-70% of cases.

Immobilize and reassure the victim, who must lie down and be kept as quiet as possible. Apply a pressure bandage immediately and immobilize the limb with a splint to reduce the spread of venom.

Loosen but do not remove the bandage if there is severe swelling. Take the victim to the hospital as soon as possible.

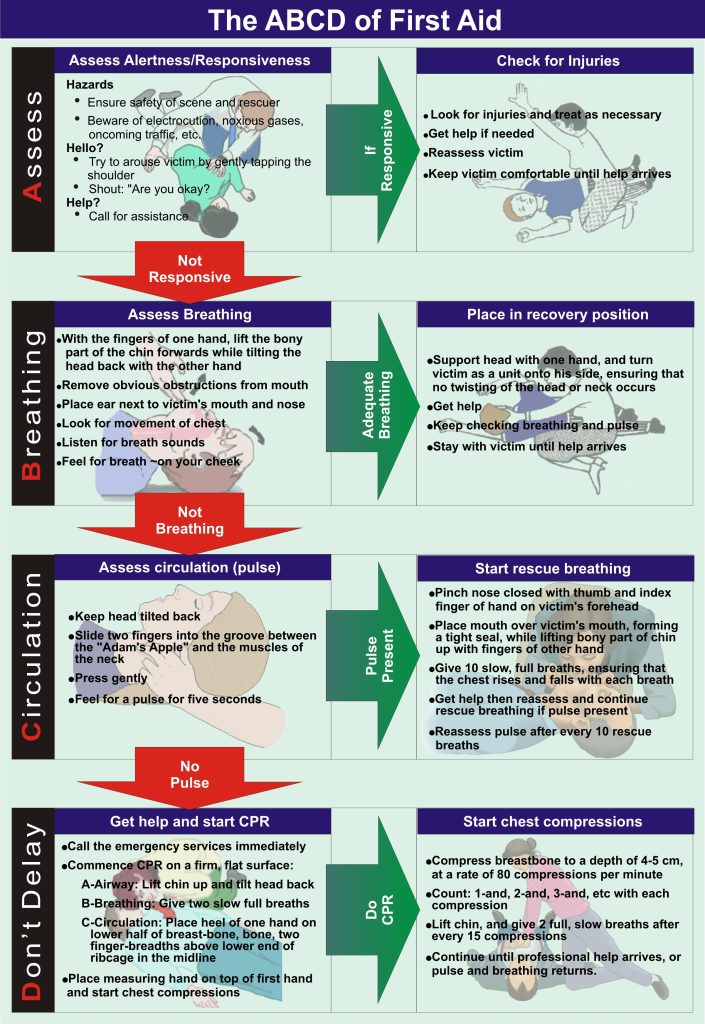

When breathing becomes difficult, CPR is an urgent necessity until medical help arrives. This is because the venom causes the central nervous system to discontinue breathing for death to ensue.

No person needs to die when bitten by a mamba if rescue breathing can be administered. Make every effort to get the victim to a hospital as soon as possible.

The Good News

Mamba bites are rare. Also, it is almost impossible to get close to a black mamba because of its extreme shyness. If walking normally, the mamba will be gone before you get within 23 m (75 feet) of it.

That is unless you are stalking something, taking care to minimise the noise you make.

It is possible that you can stumble upon an unsuspecting black mamba. The mamba will be surprised, feel threatened, and be ready to strike. This is an extremely dangerous situation.

Extreme caution must be taken when stalking during a hunt. When encountering a black mamba, forget the hunt and back away – noisily if you have to. While you are alive you can always hunt again some other time.

Case 1

On 17 February 1986, a 14-month-old girl (weight 10,6 kg.) playing indoors was bitten on the upper side of the left shin and left calf at 07:55 by a snake. The housemaid witnessed the incident and immediately sucked at the first bite, but did not notice the second bite.

The snake, a 45 cm. black mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis) was killed, identified by a herpetologist, and brought to the clinic with the child. The child reached the clinic 15 minutes after being bitten.

She was reported to have cried vigorously and vomited once on the way. On arrival at 08:00, examination found the child very pale with cold extremities and marked sweating. Her pulse rate was 96/min and she vomited for the second time shortly after arrival. There were no neurological signs.

Examination of the bite sites showed a single fang mark with 1cm of redness surrounding it on the shin; a similar bite was found on the calf but with no evidence of inflammation. The patient’s left leg was immobilised in a splint and a firm compression crepe bandage was applied to the whole limb. An intravenous line was established through a scalp vein through which half-strength Darrow’s solution was given.

The child’s condition deteriorated rapidly with clinical features of peripheral shutdown and severe shock. The breathing also became laboured with audible breath sounds and a croupy cough.

This deterioration warranted further intervention, so at 35 minutes after the bite, 100 mg. of hydrocortisone was given intravenously, followed immediately by SAIMR (South African Institute for Medical Research) polyvalent antivenom 0,5 ml. diluted 10-fold with 5% dextrose.

There was no evidence of a hypersensitivity reaction. The child was kept on her left side and vomited twice more, her back remaining in a bent backward position for several seconds during the vomiting attacks. After 20 ml. of intravenous antivenom, her condition improved, her extremities became warmer, and the pulse rate dropped to 80/min. Breathing became easier.

Further antivenom was given intravenously over 45 minutes. In all the patient received a total of 150 ml. of dextrose saline and 70 ml. of polyvalent antivenom. At 1 hour 20 minutes after the bite her condition had improved dramatically, all vital signs being stable. She was then transported to Nelspruit Hospital.

Her condition remained stable although she had two episodes of vomiting with bloodstained vomit. She arrived at Nelspruit Hospital at 11:45, 3 hours and 50 minutes after the bite. Her vital signs remained stable, the ECG was normal and she was allowed to eat and drink. Apart from bruising around the bite sites she remained alert and active, passed urine, was stable, and had a quiet night’s sleep.

She was discharged the following day, ampicillin and antitetanus toxoid having been given. On day 4, she developed gastro-enteritis, was readmitted on day 8 for further observations and baseline investigations, and was discharged 24 hours later. There have been no resulting conditions to date.

Case 2

On 9 May 1986, a 34-year-old man was bitten three times on his right ring finger by a 2,25 meter, positively identified, black mamba (D. polylepis). He reached the clinic 35 minutes after the bite.

He complained of pain at the bite site, a sensation of a swollen tongue, fullness in the head, dizziness, and a constricted feeling in the back of his throat. He was very restless, sweating, and vomited once. The blood pressure was 100/60 mm. Hg., pulse rate 112/min., and there was no evidence of paralysis. Three fang marks were found on the right ring finger with fairly marked local swelling.

He was given a total of 70 ml. of SAIMR polyvalent antivenom intravenously over 40 minutes, preceded by 500 mg. of hydrocortisone and promethazine (Phenergan) 25 mg. intravenously. The symptoms disappeared after 40 ml. of antivenom although the patient remained restless and hypotensive for 2 hours after the bite.

The patient was admitted to the clinic and observed for the next 48 hours. All vital signs remained stable during this period. He developed swelling and itching of his right hand and forearm, however, which responded well to betamethasone (Celestone) and a topical antihistamine cream. The patient was given antitetanus toxoid 0,5 ml. intramuscularly and put on ampicillin 250 mg. 4 times a day for 5 days. He was discharged fit 3 days after the bite and there have been no resulting conditions.

Reported cases of mamba bites are rare. A series from Triangle Hospital in Zimbabwe showed 7 cases of neurotoxic bites from elapid snakes; 1 case was confirmed as a black mamba bite and there was good presumptive evidence that the other bites were also due to the mamba.

There was 1 fatality in a 3-year-old child who was only given 20 ml. of SAIMR polyvalent antivenom. Another confirmed case of mamba bite in a 2-year-old black child, bitten on the head, was reported from Letaba Hospital. This child was given a total of 40 ml. of SAIMR polyvalent antivenom and survived.

In the cases reported here, several factors influenced the successful result.

Firstly, the child arrived within 15 minutes of being bitten and an intravenous line was quickly established. The first dose of antivenom was given within 35 minutes of the child being bitten. Secondly, there was no reaction to the antivenom, and 70 ml. was given.

A child should receive at least the adult dose of antivenom. The smaller the size of the victim, the greater the dose of antivenom required because of the venom-to-mass ratio. A firm crepe bandage was applied to the entire left leg.

Again in the second case, the patient arrived at the clinic within 35 minutes of being bitten, and given evidence of envenomation plus a positive identification he was treated quickly and aggressively.

The child had been bitten by a young snake between 1 – 3 months old. The mamba is born with 2 – 3 drops of venom per fang (an adult snake having 12 – 20 drops per fang) and 2 drops of venom only are required to kill an adult human, thus making the young mamba a very dangerous snake. The adult probably received a large amount of venom after sustaining 3 deep bites from a fully-grown adult snake.

To summarize, the steps in the treatment of a mamba bite are as follows:

Immobilization of the affected limb and firm compression bandage of the part above the bite may effectively prevent venom absorption.

Antivenom should be used as soon as possible, in appropriate dosage and intravenously. There is no ‘standard dose’ but as a guideline, 20 – 40 ml. initially to a total dose of 60 – 80 ml. in an adult and in some cases up to 200 ml. and at least as much if not more in a child (both of the cases reported here received 70 ml. of polyvalent antivenom). Adrenaline and hydrocortisone should be readily available, preferably already drawn up, to counteract anaphylaxis should this occur.

Equipment and medications for cardiopulmonary resuscitation should be on hand and ready for immediate use.

In a referral center, full intensive-care management of respiratory failure, cardiac arrhythmias, and generalised paralysis may be necessary.

From SAMJ VOL 72 1 AUGUST 1987

The Antivenom

The erstwhile SAIMR now falls under the National Health Laboratory Services and is now the South African Vaccine Producers. Antivenom production began at the South African Institute of Medical Research (now known as NHLS- National Health Laboratory Service) as early as 1928. The initial antivenoms produced were limited to Cape Cobra & Puff Adder, and in 1938 the venom from the Gaboon Adder was incorporated into the immunization schedule.

In 1941 this polyvalent range was expanded to incorporate the venom from the Rinkhals. During the 1950s & 1960s, several monovalent & trivalent antivenoms to the Southern African mambas were developed (Black, Green & Jamesons Mamba), and by 1971 the original polyvalent antivenom was extended to incorporate these valencies.

Other venoms later incorporated into the immunization schedule in the 1970s were the Snouted cobra, (previously known as the Egyptian Cobra), Forest cobra & the Mozambican Spitting cobra resulting in the 10 valencies making up the current polyvalent, which has remained unchanged to date.

South African Vaccine Producers’ website is at http://www.savp.co.za and they can be contacted at +27 11 3866000 or +27 11 386-6078 and faxed at +27 11 3866016.

Their address is 1 Modderfontein Road, Sandringham Johannesburg, or PO Box 28999 Sandringham 2131, Republic of South Africa.