You’re back from safari but you seem to always be tired, can’t concentrate, and feel listless and sleepy. Your wife is fed up and you can’t make it through meetings at work without snoring.

Remember cooling off in the Zambezi while your PH kept the Crocs away with his .375 magnum? Remember walking through that stream while tracking that trophy dagga boy?

Good news, bud: it is not only because you miss Africa and that you are way over 40 that you are feeling this way. When your PH slapped you on your back and said that Africa becomes part of you, he meant it literally and figuratively: Africa is not only in your heart – you could be harbouring Africa’s common water-borne parasite in your bloodstream.

The African bush is a place of beauty, tranquility, and magnificence but is also home to some of the world’s most deadly diseases. One of them, lurking in streams, rivers, and pools has a dark side to it which could cause life-threatening complications.

t is a common, chronically debilitating, and potentially lethal disease affecting an estimated 200 million people, half of whom live in Africa, with 600 million people being at risk.

It is called Bilharzia or Schistosomiasis.

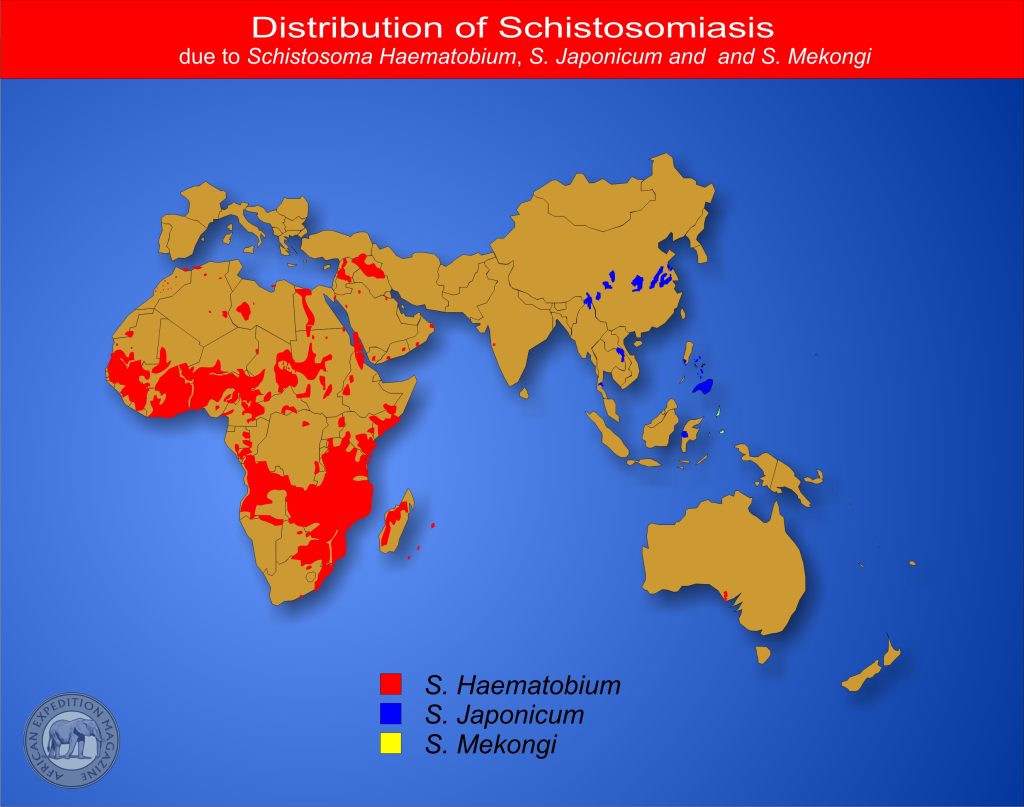

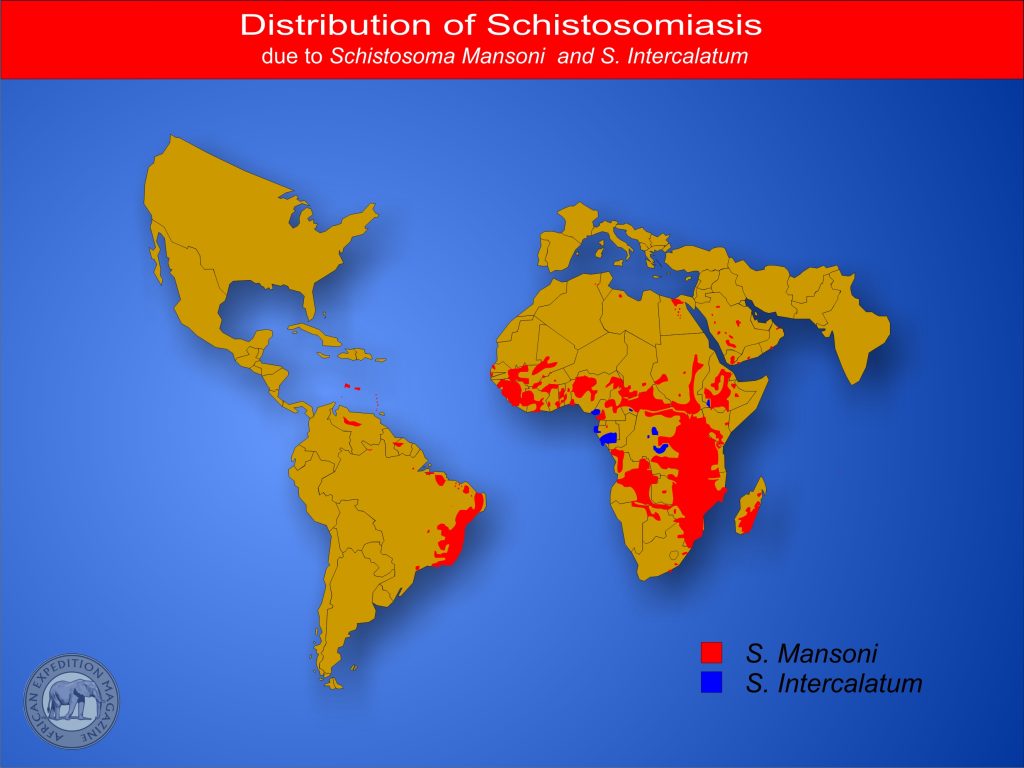

Schistosomiasis is most prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa. This infection occurs throughout the tropics and subtropics. It is endemic to 74 countries.

Bilharzia is a parasitic infection caused by Schistosoma blood flukes. Five species of Schistosoma infect humans:

Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma intercalatum cause intestinal schistosomiasis while Schistosoma haematobium causes urinary schistosomiasis.

Schistosoma japonicum and Schistosoma mekongi cause Asian intestinal schistosomiasis.

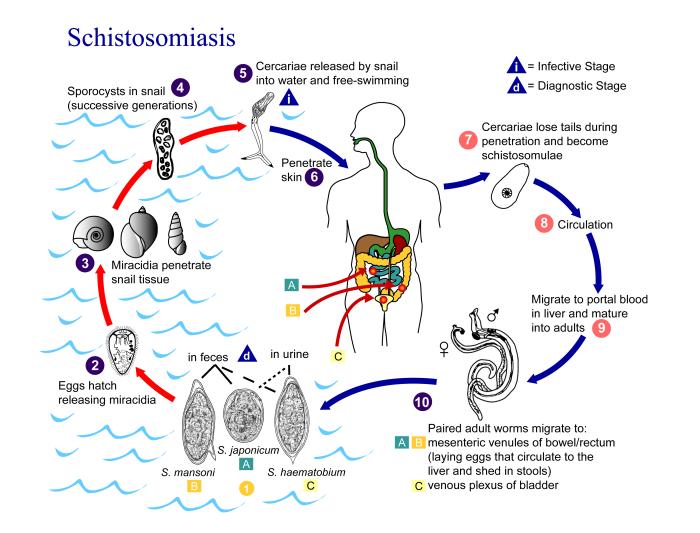

Schistosoma flukes have a complex life cycle involving specific freshwater snail species as intermediate hosts. Bilharzia eggs are released into the environment from infected individuals, hatching on contact with fresh water to release free-swimming miracidium.

Miracidia infect fresh-water snails by penetrating the snail’s foot. Infected snails release large numbers of small, larvae called cercariae, capable of penetrating the unbroken skin of humans. Even brief exposure to contaminated water can result in infection.

Cercariae emerge constantly from the snail host in what is called a circadian rhythm. This is dependent on ambient temperature and light. Cercariae are highly mobile and can sink to maintain their position in the water or swim upwards if stimulated by water turbulence, shadows, and some chemical substances found on human skin.

Cercariae secrete enzymes that break down human skin and make penetration possible. “Swimmers itch” occurs 1 day after penetration. It is an itchy rash caused by the death of cercariae upon skin penetration. The rash resolves spontaneously within 10 days and is rare in endemic areas.

Free-swimming Miracidia enter the snail by penetrating the snail’s foot. As the cercaria penetrates the skin it transforms into a migrating schistosomulum stage. Here it stays in the skin for a few days while locating a small vein to transport it to the lungs of the human host. From here it migrates to the liver.

Juvenile worms from some species develop oral suckers and the worms start feeding on red blood cells. Worms pair up and:

- S. mansoni and S. japonicum relocate to the intestine or rectal veins

- S. haematobium migrate from the liver to the venous plexus of the bladder, ureters, and kidneys.

Worms reach maturity in eight weeks, at which time they begin to produce eggs. Adult worms may produce 300 to 3000 eggs per day. Many of the eggs pass through the intestinal or bladder wall into the feces or urine.

Some eggs released by the worm pairs become trapped in the veins or will be washed back into the liver, where they will become lodged. Worm pairs can live in the body for an average of four and a half years, but may persist up to 20 years.

Trapped eggs mature normally, and elicit a vigorous immune response. The eggs themselves do not damage the body but due to the immune response severe complications may arise.

Symptoms

Schistosomiasis is a chronic disease. Many infections are asymptomatic, with mild anemia and malnutrition being common in endemic areas. Katayama fever however is a rare but potentially lethal illness occurring 1 to 3 months after the primary infection.

Symptoms include fever, headache, chills, sweating, diarrhoea, cough, enlarged liver and glands, and urticaria.

Clinical features of chronic Bilharzia include fatigue, abdominal pain, cough, and diarrhoea. Various systems can be involved.

Lung disease: Fatigue, dizziness and chest pain may develop due to embolizing eggs.

Liver disease: Abdominal distension, enlarged liver, fluid accumulation in the abdomen, dilated blood vessels in the esophagus.

Intestinal disease: Embolizing eggs may cause chronic inflammation of the large bowel, bloody diarrhoea, anemia, and rectal prolapse.

Central nervous system disease: Epilepsy, paraplegia, and bladder dysfunction.

Typhoid bacteria may colonize the adult worms providing a source of recurrent typhoid attacks.

Diagnosis of Bilharzia is usually confirmed by serologic studies (a blood test) or by finding Bilharzia eggs on microscopic examination of stool or urine.

Bilharzia eggs can be found as soon as 6-8 weeks after exposure, but are not always detectable. Blood tests in the exposed, asymptomatic traveler should ideally be performed 6-8 months following exposure.

Safe and effective drugs are available for the treatment of Bilharzia and your healthcare worker or Family physician will prescribe medication that will kill the adult Bilharzia worms.

How can I prevent Schistosomiasis?

Avoid swimming or walking in freshwater in countries in which schistosomiasis occurs.

Drink safe water.

You should either boil water for 1 minute or filter water before drinking it. Boiling water for at least 1 minute will kill any harmful parasites, bacteria, or viruses present. Iodine treatment alone will not guarantee that water is safe and free of all parasites.

Heat your bath water for 5 minutes at 150°F. Water held in a storage tank for at least 48 hours should be safe for showering.

Dr. Swart has been involved in Communicable disease control since 2004 and is an authority on Malaria, and tropical and infectious diseases in Africa.

Vigorous towel drying after an accidental, very brief water exposure may help to prevent the Schistosoma parasite from penetrating the skin.

Do NOT rely on vigorous towel drying to prevent Bilharzia.