In Part 1 we had a glimpse into the reality of what it means to survive by hunting. What a contrast to us modern-day hunters who kill to have hunted and do not have to, as a matter of life or death, hunt to kill. Even if we come back from the hunt empty handed there are lavish meals awaiting us. We sleep in comfort – five-star hunting lodges on the upper end of the spectrum and if we really want to “rough it” we sleep on camp stretchers in luxury safari tents with en suite toilets and hot showers.

We arrive back at camp to a roaring bonfire prepared by the camp staff, and there is enough to drink to start a lucrative shabeen. We are flown in luxury aircraft or driven to the hunting grounds in comfortable vehicles, and our scoped rifles with fast, flat-shooting bullets make shots at 250m, nothing out of the ordinary. How different from real hunters who had only their feet for transport and primitive weapons with severe limitations at their disposal.

Hunting is becoming a highly debated issue as animal rights and anti-hunting groups become more vocal and in some instances, even militant. Whereas “sport” and “trophy” hunting is to them something reprehensible some (not all) will concede that subsistence hunting, where people are dependent on the animals they hunt or fish they catch for their very survival, is justifiable.

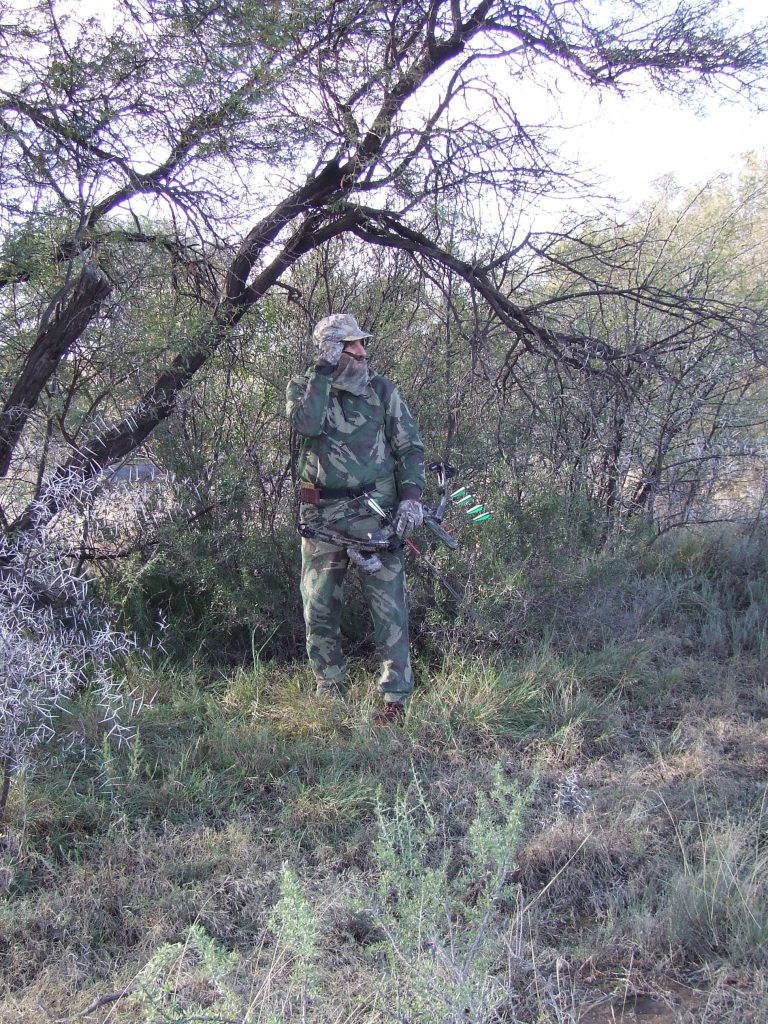

A number of years ago, this got me thinking, and I did some “survival” hunting. This involved going out into the bush with only my bow, some basic survival tools, and a little food to start off with for an extended period of time (5-10 days). Once my food and water ran out, I would then be forced to live off what nature provided. What I could successfully hunt, I ate and my diet was supplemented by what I could find in the way of edible plants and fruits. Water was, at certain times of the year, scarce and had to be carefully conserved.

I would also have to go to great lengths to purify what water I could find before drinking it or be reasonably sure that it was clean enough to drink (Figure 1).

Diarrhoea and vomiting caused by contaminated water is something you do not want to be subjected to in a wild bush environment – it can be fatal – and waiting for water to boil and then cool down enough when you are really thirsty is a great lesson in patience. It was a great opportunity to put bush and survival skills to the test and, although I would return sometimes leaner than when I departed, they were wonderful experiences – a type of hunting I would highly recommend and which should be more acceptable to anti-hunters as the hunter is exposed to greater challenges and risks and eats what is harvested because he is “living off the land” – subsistence hunting (well …sort of). It gives some insight into just how hard it is to “live off the land” and teaches one to savour and appreciate every mouthful of food and water.

You must be out in the bush long enough to REALLY get hungry and to be REALLY exposed to the risk of becoming dehydrated for the exercise to be meaningful. I would recommend a minimum of 7 days and preferably 10-14 days. This may, in terms of time required, be a problem for some but if you only do it once in a lifetime it will be a never to be forgotten experience.

It is not a type of hunting recommended for the novice who has little bush knowledge and survival skills as there are real risks involved. The experience can be made more challenging by:

- Practicing making fire using primitive methods (Figure 2).

- Sleeping in the bush on the ground (Figure 3).

- Taking a bow and only 5 arrows or rifle and only 5 rounds of ammunition

- Taking a minimum amount of equipment – bow/arrows or rifle/ammo, sleeping bag, knife, flint and steel, and water bottle. That, apart from the sleeping bag and rifle, is about all a Kalahari bushman carries with him. He may carry a karos (blanket made of animal skin) in lieu of a sleeping bag.

- Taking a minimum amount of food and water with you to begin with. The idea is that you MUST run out of supplies within a day or two which will force you into “subsistence” mode. Water and food must be found or hunted from that point onwards.

- Do not carry any form of communication with you such as a cell phone or two-way radio. “Cutting yourself off” from civilization and support structures is one of the “features” of survival hunting which makes it more challenging and, although riskier, more rewarding.

- If possible conduct the survival hunt in big game country. This is not advisable for the inexperienced however.

Survival hunting is not for the faint-hearted – it can be pretty scary at night, on your own, in big game country – especially if you hear lions roaring or the “sawing” sound of a leopard wending its way up a dry riverbed. That is when you learn the value of fire and how important it is to have enough fuel on hand to quickly build it up so that it can be a predator deterrent. You select your nightly camping and sleeping spot with great circumspection and learn to sleep with one eye open.

You hunt with greater care knowing that if you duff an opportunity to “bag” something you will be going to bed hungry (Figure 4).

No fancy lodge with a 5-course meal waiting on your return! It makes you a better hunter. You also learn to be more attentive in the bush to potential danger and become more experienced in learning to find food and water.

And yes, occasionally there would be the great reward of a successful hunt and an appreciation of what goes through the heart of a bushman when his arrow has flown true, the poison has worked and he and his clan would not go to bed with the gnawing pangs of hunger (Figure 5).

All in all, it is the most rewarding and fulfilling type of hunting I have ever done, and the “antis” will (hopefully) have less to gripe about because there are times when you may not successfully shoot anything and will return hungrier, thinner, grubbier, smellier but a whole lot wiser and a whole lot closer to your Creator. It is more than worth it and is highly recommended.